Nocardia keratitis mimicking superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis and herpes simplex virus

Nocardia keratitis mimicking superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis and herpes simplex virus

Eileen L. Chang

aDepartment of Ophthalmology, Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, NY, 11554, USA

Rachel L. Chu

bRenaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, 11794, USA

John R. Wittpenn

cDivision of Cornea and Refractive Surgery, Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island, Rockville Centre, NY, 11570, USA

Henry D. Perry

aDepartment of Ophthalmology, Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, NY, 11554, USA

cDivision of Cornea and Refractive Surgery, Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island, Rockville Centre, NY, 11570, USA

Abstract

Purpose

Nocardia keratitis is a rare type of infectious keratitis and may mimic other corneal diseases and lead to delay in diagnosis. This case illustrates how Nocardia often escapes accurate diagnosis due to its insidious onset, variable clinical manifestations, and unusual characteristics on cultures.

Observation

The patient presented with an epithelial defect and superior pannus and scarring, which was misdiagnosed as superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis. Repeat corneal scraping cultures, smears, and conjunctival biopsy were necessary to elucidate the diagnosis. It can be effectively treated with the intravenous preparation of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 80 mg/mL (brand name SEPTRA) used topically as eye drops.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of Nocardia keratitis relies on a high clinical suspicion and a prompt corneal scraping with culture. Due to its potential for rapid resolution with early therapy, it is important to isolate Nocardia early in its disease course.

Importance

Topical amikacin had been the standard of care for Nocardia keratitis for many years. However, recently there is increasing resistance of Nocardia to amikacin. SEPTRA offers an alternative therapy. Nocardia keratitis mimics other infectious and inflammatory etiologies so rapid diagnosis and treatment is critical in the prevention of long-term complications.

1. Introduction

Nocardia are a group of aerobic, gram-positive, and catalase-positive bacteria in the shape of long, thin, and branching filaments that stain weakly acid-fast on Ziehl-Neelsen1. Nocardia asteroides is the most commonly reported species to cause Nocardia keratitis. It is classically described with an appearance of stromal infiltrates in a wreath-like pattern and may be associated with tiny epithelial calcifications often near the limbus adjacent to pannus-like areas of increased vascularity.2,3 Culture on blood agar may occasionally lead to a consideration of contamination due to the tendency for prominent areas of calcification on the agar.2 Nocardia keratitis is seen more frequently in young males, especially those who live in rural areas.3,4 As Nocardia is the most common bacteria found in soil, corneal trauma and contact with soil predispose those in rural areas to infection. Other risk factors for Nocardia keratitis include contact lens wear, ophthalmic surgery, and topical corticosteroids.5, 6, 7, 8

This unique case of Nocardia keratitis focuses attention on the variability of presentation and the possibility of a prolonged clinical course over months. The multiple misdiagnoses suffered by this patient highlight how this pathogen is elusive and often discovered late in the clinical course leading to permanent ocular sequelae.

2. Case presentation

A 41-year-old male contact lens user without history of corneal trauma or soil contact presented with a three-week history of pruritus, photophobia, and excessive tearing of the right eye. He was initially found to have a corneal abrasion and started on topical tobramycin 0.3% QID, which aggravated his symptoms. The patient was then referred to an ophthalmologist who added loteprednol 0.5% daily. The patient failed to respond to this therapy and was sent to a corneal specialist. On initial presentation, the patient’s best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in the right eye was 20/20–3. Anterior segment exam was significant for bilateral blepharitis, right floppy eyelid, right trace perilimbal injection, 2+ superior palpebral conjunctival injection, and a new right corneal scar with irregular epithelium lacking definitive boundaries superiorly at 12 o’clock. Given the pattern of injection, recurrent discomfort, and subjective complaint of itchiness, superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK) was considered. The corneal specialist trialed a course of ofloxacin 0.3% and then increased loteprednol 0.5% to BID dosing.

On two-week follow-up, the patient displayed symptomatic improvement. However, the clinical exam demonstrated new dendritiform lesions developing at the peripheral edge of the corneal scar. Treatment for presumed herpes simplex keratitis (HSV) was initiated with a course of oral valacyclovir TID and topical ganciclovir 0.15% QID. Additionally, the patient was sent for corneal cultures to rule out fungal keratitis. Follow-up results were negative for fungi.

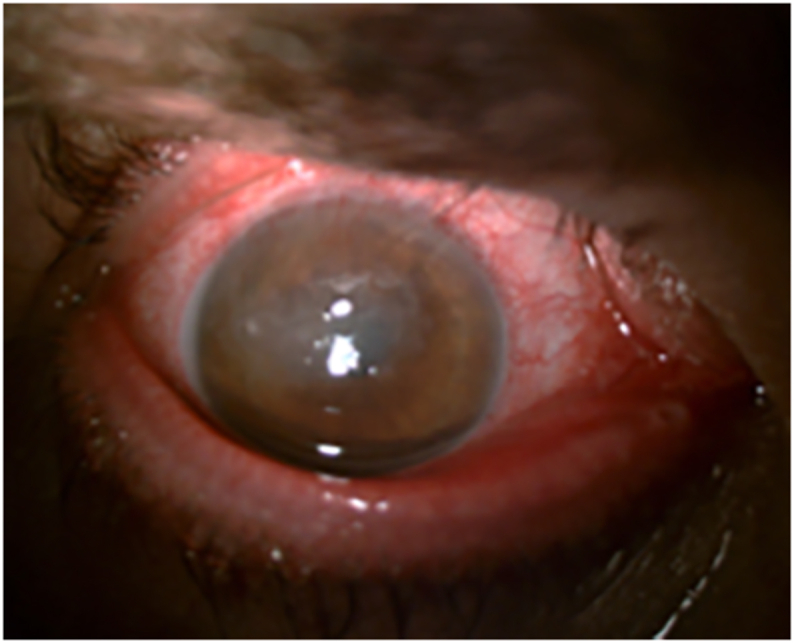

The patient returned in one month with worsening symptoms. At this time, his corneal scar displayed anterior stromal scarring with new overlying neovascularization and an advancing edge of irregular epithelium (Fig. 1). Keratic precipitates and anterior chamber inflammation were absent. At this point, the diagnosis of HSV interstitial keratitis was considered. The topical medications were switched from loteprednol to difluprednate 0.05% QID; the patient was restarted on valacyclovir TID.

Clinical photograph of the patient’s right eye on initial presentation to second corneal specialist (3 months from first symptoms) demonstrating superior pannus, anterior stromal scarring, conjunctival injection, and floppy eyelids.

After returning from vacation overseas, the patient followed up with the corneal specialist with minimal improvement. Given the failure to respond to herpetic treatment, a superior conjunctival resection for presumed SLK and corneal scrapings were taken from the right eye where the cornea was abnormal. A ProKera Slim™ amniotic membrane was placed over the defect and prophylactic ophthalmic antibiotics were started. The patient was maintained on oral valacyclovir TID, topical difluprednate 0.05% BID, and topical ofloxacin 0.3% as antibiotic prophylaxis for a few days. Corneal scrapings did not reveal findings suggestive of SLK or microbial keratitis when evaluated.

One week later, the patient reported dramatically decreased vision with severe photophobia and difficulty opening the right eye. Visual acuity was 20/400 with the ProKera Slim™. At this point, the corneal scraping was 95% healed so the ProKera Slim™ was removed. No further stromal infiltrates were noted. All medications were discontinued except bacitracin-polymyxin B. On subsequent follow-up one week later, the patient was referred to another corneal specialist for consultation. At this visit, a repeat corneal Gram stain and a Papinicolau stain were positive for filamentous rods and Nocardia was suspected (Fig. 2). Therapy was initiated with trimethroprim-sulfamethaxazole (SEPTRA) 80 mg/mL in the right eye every 2 hours. One week later, cultural identification was confirmed for Nocardia asteroides and sensitivities showed resistance to amikacin. After three months of unabated progression of his signs and symptoms, the patient showed clinical improvement in three days. However given the prolonged course, he required an additional month of therapy. The patient healed with a subepithelial scar and neovascularization. At this point, SEPTRA was discontinued. The final visual acuity of the right eye was 20/30. Interestingly, the conjunctival biopsy was revisited and showed no signs of Nocardia.

Papinicolau stain magnified 400X of corneal scraping demonstrating branching filaments characteristic of Nocardia asteroides.

3. Discussion

The usual presenting symptoms of Nocardia keratitis include pain, photophobia, blepharospasm, and lid swelling. Nocardia keratitis frequently runs a protracted benign course, but acute severe cases have been seen.9, 10, 11 Superficial granular infiltrates coalesce into a white plaque of variable size over time and result in corneal ulceration that is often superior in location. In addition to the classic finding of patchy wreath-like anterior stromal infiltrates, other presenting features include pseudodendritic epithelial defect, subepithelial infiltrate, persistent epithelial defect, and/or neovascularization into the cornea.2,10

Diagnosis of Nocardia keratitis is often delayed due to several factors. First, symptoms can have an insidious onset and patients may not initially seek medical care. The variable clinical presentations can mimic other forms of keratitis, such as mycotic or atypical mycobacterial infection.12 The clinician needs to have a high clinical suspicion as Nocardia grows slowly on culture. A prompt corneal scraping and culture should be performed with clinical suspicion. However, this may yield negative results as in this case. Nocardia corneal scrapings are positive for gram-positive, branching filaments that stain weakly acid-fast on Ziehl-Neelsen and black on Gomori methenamine silver.1

Nocardia keratitis can be misdiagnosed as superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis if the disease is located in the superior cornea, as in this case. SLK is characterized by inflammation of the superior bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva in addition to superior corneal vascularization that may appear as a pannus.13 SLK will often demonstrate punctate staining with fluorescein and/or rose Bengal. There can also be localized filamentary keratopathy in one-third of cases. Diagnosis involves obtaining a corneal scraping for Giemsa stain, which typically shows enhanced keratinization, poor nuclei, and hyalinized cytoplasm. Corneal scrapings from this case were not diagnostic for SLK. Treatment modalities include use of topical silver nitrate 1%, anti-inflammatory agents, and conjunctival resection.14,15

Another confounder for Nocardia may be HSV as in this case. At one point in the presentation, a dendritiform lesion was noted suggesting HSV epitheliopathy. A few weeks later, corneal neovascularization and haze developed which appeared clinically as an HSV interstitial keratitis. This clinical picture of apparent recurrence can be quite convincing for herpetic interstitial keratitis. However, the steroid treatment may have exacerbated the Nocardia infection.

Nocardia keratitis is most effectively treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or amikacin; the latter is considered the drug of choice for all species of Nocardia.16 However, resistance to amikacin, as in this case, has been previously described.17 The intravenous preparation of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole can be used directly as eye drops, typically in a dosing of 16 mg/mL trimethoprim and 80 mg/mL sulfamethoxazole. Amikacin is typically used in the concentration of 2.5% and is prepared by adding 8 mL of artificial tears to 2 mL of the intravenous preparation of 125 mg/mL amikacin.6 Of note, systemic antibiotics do not add benefit to the clinical outcome of Nocardia keratitis. Steroids worsen the symptoms of Nocardia keratitis, potentially leading to complications such as corneal perforation, scleritis, and endophthalmitis. Thus, it is critically important to identify the causative organism early as routine steroid use for falsely suspected viral keratitis and SLK exacerbates the underlying condition.

Nocardia keratitis responds well to medical therapy. If treatment is started early in the course, the corneal ulcer tends to heal rapidly with mild peripheral vascularization. The infiltrate resolves with minimal scarring and forms a fine superficial nebular opacity. Visual acuity improves rapidly and the end result is a barely visible residual stromal haze.

4. Conclusions

Nocardia are a rare cause of infectious keratitis. Early diagnosis and treatment of Nocardia keratitis are difficult because of its infrequent occurrence and variable clinical manifestations. We describe a case of Nocardia keratitis that was initially misdiagnosed and treated with multiple antibacterial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory agents. Due to its superior location, SLK was considered and prompted a superior conjunctival resection that disproved the diagnosis. Of note, the initial cultures were negative and it was only after a second corneal scraping that Nocardia was correctly identified by cytology and confirmed by cultures. Once diagnosed, this case of Nocardia keratitis responded effectively to treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SEPTRA) in the setting of amikacin resistance.

Patient consent

The patient consented to publication of the case in writing and orally.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Eileen L. Chang: Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Rachel L. Chu: Writing – original draft. John R. Wittpenn: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Henry D. Perry: Supervision, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

No funding or grant support. There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for any of the authors listed. All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for Authorship.

References

Content retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7900621/.