An impressive case of complete traumatic maxillofacial degloving.

A woman sustained severe facial injuries in a rollover automobile accident after the driver lost control of the small car, which was carrying five passengers and not equipped with airbags. The 30-year-old woman was in the back seat and not wearing a seatbelt at the time of the accident. Although one witness claimed that no one was ejected from the vehicle, the extent of the victim’s injuries suggested otherwise. The woman was first taken to a low-complexity hospital for primary care, including a tracheostomy, before being transferred to a high-complexity trauma unit nine hours after the accident.

Upon arrival at the trauma unit, the patient was conscious and oriented but pale, tachypneic, and tachycardic. A cranial tomogram revealed no neurosurgical lesions, but physical examination showed severe facial trauma with a broad laceration–contusion injury with a high degree of contamination, including sticks, grass, sand, and food scraps. The injury extended from the right parotid-masseter region, contoured below the chin, and terminated in the left temporal region, forming a large flap with the entire area of the face.

The intensity of the trauma resulted in the destruction of anatomic structures, with complex fractures in the upper and middle thirds of the face. The fronto-naso-ethmoidal regions suffered substantial bone loss, and the zygomatic-orbital complex sustained bilateral damage to the medial walls and orbital floors. A transverse fracture extended through the palatine process, with the breakage of the greater palatine arteries, which partially interrupted the blood supply to the maxilla, attached only by its vestibular mucosa. Despite the severity of the injuries, the patient’s vision remained intact, as confirmed by routine ophthalmological examination.

Fig. 1

(A) Frontal view of the patient with facial flap down showing communication between the nasal and oral cavities after severe trauma; (B, C) right and left profiles of the patient. Note that the whole mouth and a large fragment of jaw were kept in place only by the soft tissue of the buccal vestibule.

The patient was rushed to the operating room for immediate medical attention. With the aid of general anesthesia administered through the tracheostomy, the medical team conducted a thorough exploration of the extensive facial wound and ensured rigorous surgical cleaning. Hemostasis of the injured vessels was performed, and the blood volume was restored using 2000 ml of lactated Ringer’s solution and two red blood cell concentrates. The primary surgical objective was to reconstruct the nasal structures, allowing for the permeability of the upper airways. Additionally, the extrinsic musculature of the orbits was repositioned, and the maxilla was repositioned using maxillomandibular fixation with Erich arch bars for maintaining the dental arches (refer to Fig. 2). In the initial surgery, only the bone fractures exposed by the trauma, namely the anterior wall of the frontal sinus, left zygomatic arch, and nasal bones, were treated. The rest of the fractures were left for a subsequent elective surgery, as discussed below.

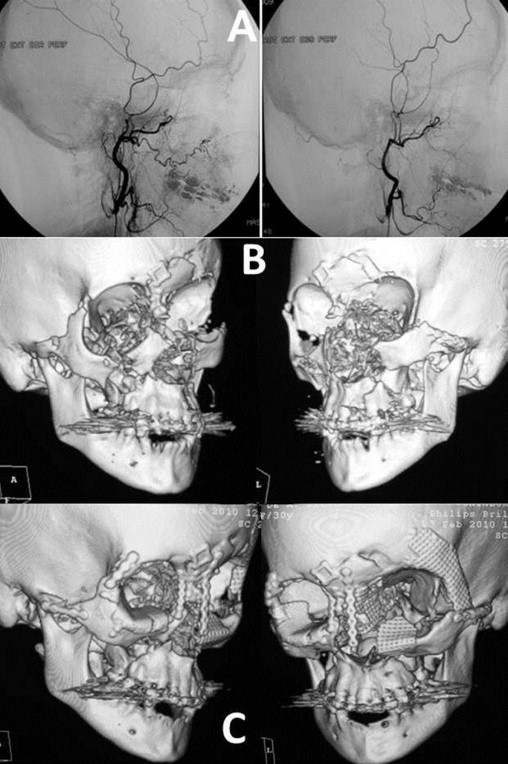

Fig. 2

(A, B) The patient after copious washing of the wound with saline, removal of devitalized tissue and fixation of fractures of the frontal bones and nasal and left zygomatic arches with titanium miniplates; (C) repositioning of the maxilla; (D) the immediate postoperative period.

Following the initial surgical procedure, which lasted 6 hours, the patient was transferred to the post-anaesthesia care unit where she was conscious, hemodynamically stable, and did not require mechanical ventilation. During this time, she was administered venous antibiotics, pain killers, and enoxaparin prophylaxis for venous thrombosis. After 12 hours, she was transferred to the infirmary of the oral-maxillofacial surgery and traumatology sector to await clinical improvement and the planning of subsequent surgery.

Over the next 72 hours, small perforations with an insulin needle were made daily to assess the perfusion and coloration of the vestibular and palatine mucosae in order to establish an early diagnosis of any sign of bone necrosis, but none occurred. There was no need for coadjuvant therapy, such as hyperbaric oxygenation.

Ten days later, new imaging examinations were performed, including an angiogram, which revealed adequate vascularization of the face and areas suggesting vascular neoformation. Despite the injury to her left facial nerve and aesthetic impairments, characterized by traumatic telechantus and a drooping right eyelid, the patient’s progress was deemed quite satisfactory. Her masticatory function had been preserved and there were no signs of tissue necrosis or infection.

The original authors could not be found. If you’re an author or have any information about the authors, please contact us at medihelplife@gmail.com