Complications of thyroidectomy for large goiter

Toufik Berri1,& and Rachida Houari2

Patient and observation

A 50-years-old woman, hypertensive, hospitalized for a large cervical mass appeared 30 years ago. In the family history, her mother, sisters and cousins underwent a surgery for MNG.

Despite of the large volume of the mass, the patient never described signs of cervical compression whatsoever respiratory, digestive, laryngeal, vascular or neurologic signs. She never suffered from thyroid dysfunction. Her neck was deformed by the voluminous formation classified grade III according to the WHO modified classification. The mass took the front and the two sides of the neck. Its surface was embossed and covered by a thin normal skin. There were some veins of the collateral circulation limited to the neck. The goiter measured 18 × 11 cm (Figure 1). The mass was firm, painless, and mobile with the swallowing movements. Lymphadenopathy research was difficult and found no palpable lymph nodes.

Frontal view of the goiter

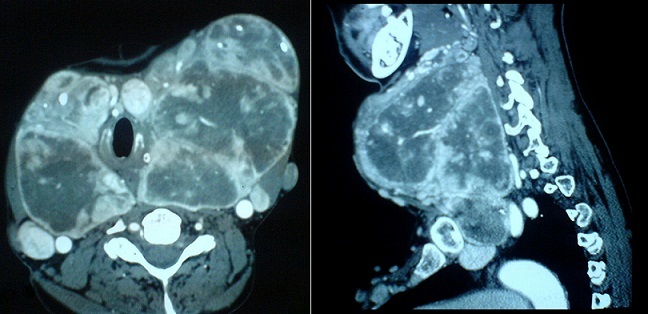

The laboratory tests (T3, T4 and TSH) were normal. Thoracic radiography showed a large cervical opacity roughly round and strewn with microcalcifications associated with a right eccentricity of the trachea (Figure 2). Cervical and chest CT revealed the presence of a partially calcified thyroid mass slightly plunging in the anterior mediastinum. It took heterogeneously the contrast and then evocate a large MNG. The trachea was surrounded by the goiter, slightly narrowed and right deviated as well as the lower part of the larynx. The right and left vascular axes of the neck (carotid artery and jugular vein) were deviated backward (Figure 3).

Chest X-ray: the right eccentricity of the trachea

CT scan of the neck

The patient underwent a surgery for her enormous MNG slightly plunging in the mediastinum. Endotracheal intubation was relatively easy by the laryngoscope. The incision performed was a Kocher cervicotomy. There was a multinodular, hypervascularized goiter. Its lower end plunges behind the sternal manubrium. The larynx was deviated towards the right side. The total thyroidectomy was performed in two steps: initially a right lobo-isthmectomy, then the left lobectomy. The retrosternal part of the goiter was released using the finger by the same incision (Figure 4). Both recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLN) were not identified because of the hemorrhage. One parathyroid gland was accidently devascularized and was autotransplanted to the ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid muscle. The operation was finished by double aspiration drainage.

Postoperative specimen

In the first hours after surgery, the patient developed a large cervical hematoma. She was readmitted to the operating room, and after evacuation of the hematoma there was no vessels bleeding. The operation was completed with a double suction drainage.

In the immediate postoperative period, the patient developed hemodynamic collapse requiring the introduction of dobutamine. After 48 hours of hemodynamic support, the blood pressure stabilized and dobutamine was stopped.

Histological study concluded in multinodular colloid goiter. The patient was discharged from the hospital after 20 days in good health.

References

References

1. WHO, UNICEF, and ICCIDD. Indicators for assessing iodine deficiency disorders and their control programmes. 1993 http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1993/WHO_NUT_93.pdf. Accessed 20 August 2013.2. Rugiu MG, Piemonte M. Surgical approach to retrosternal goitre: do we still need sternotomy? Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2009;29(6):331–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]3. Abboud B, Sleilaty G, et al. Morbidity and mortality of thyroidectomy for substernal goiter. Head Neck. 2010;32(6):744–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]4. Blank RS, de Souza DG. Anesthetic management of patients with an anterior mediastinal mass: continuing professional development. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58(9):853–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]5. Slinger P, Karsli C. Management of the patient with a large anterior mediastinal mass: recurring myths. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007;20(1):1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]6. Rosato L, Avenia N, Bernante P, De Palma M, et al. Complications of thyroid surgery: analysis of a multicentric study on 14,934 patients operated on in Italy over 5 years. World J Surg. 2004 Mar;28(3):271–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]7. Reeve T, Thompson NW. Complications of thyroid surgery: how to avoid them, how to manage them, and observation on their possible effect on the whole patient. World J Surg. 2000 Aug;24(8):971–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]8. Rosato L, Nasi PG, Porcellana V, Varvello G, et al. Unilateral phrenic nerve paralysis: a rare complication after total thyroidectomy for a large cervico-mediastinal goitre. G Chir. 2007 Apr;28(4):149–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]9. Stavrakis AI, Ituarte PH, Ko CY, Yeh MW. Surgeon volume as a predictor of outcomes in inpatient and outpatient endocrine surgery. Surgery. 2007 Dec;142(6):887–99. discussion 887-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]10. Randolph GW, Dralle H, et al. Electrophysiologic recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring during thyroid and parathyroid surgery: international standards guideline statement. Laryngoscope. 2011 Jan;121(Suppl 1):S1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]11. Proye C, Grégoire M, Lagache G. Les goitres plongeants – Considérations anatomo-cliniques et chirurgicales. Lyon Chir. 1982;78:19–25. [Google Scholar]

Articles from The Pan African Medical Journal are provided here courtesy of African Field Epidemiology Network

Copyright and license information

Copyright © Toufik Berri et al.The Pan African Medical Journal – ISSN 1937-8688. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Original source

Author information

1Department of surgery, Tourabi Boudjemaa Hospital, Bechar, Algeria2Department of surgery, Benzardjab Hospital, Oran, Algeria&Corresponding author: Toufik Berri, Department of surgery, Tourabi Boudjemaa Hospital, BP 71 Maghnia 13300, Tlemcen, Algeria