Neovascularization of coronary tunica intima (DIT) is the cause of coronary atherosclerosis.

1602 Samuel Drive, Madison, WI, 53717, USA

Corresponding author:

Vladimir M Subbotin: moc.liamg@nitobbus.m.rimidalv

Background

An accepted hypothesis states that coronary atherosclerosis (CA) is initiated by endothelial dysfunction due to inflammation and high levels of LDL-C, followed by deposition of lipids and macrophages from the luminal blood into the arterial intima, resulting in plaque formation. The success of statins in preventing CA promised much for extended protection and effective therapeutics. However, stalled progress in pharmaceutical treatment gives a good reason to review logical properties of the hypothesis underlining our efforts, and to reconsider whether our perception of CA is consistent with facts about the normal and diseased coronary artery.

Analysis

To begin with, it must be noted that the normal coronary intima is not a single-layer endothelium covering a thin acellular compartment, as claimed in most publications, but always appears as a multi-layer cellular compartment, or diffuse intimal thickening (DIT), in which cells are arranged in many layers. If low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) invades the DIT from the coronary lumen, the initial depositions ought to be most proximal to blood, i.e. in the inner DIT. The facts show that the opposite is true, and lipids are initially deposited in the outer DIT. This contradiction is resolved by observing that the normal DIT is always avascular, receiving nutrients by diffusion from the lumen, whereas in CA the outer DIT is always neovascularized from adventitial vasa vasorum. The proteoglycan biglycan, confined to the outer DIT in both normal and diseased coronary arteries, has high binding capacity for LDL-C.

However, the normal DIT is avascular and biglycan-LDL-C interactions are prevented by diffusion distance and LDL-C size (20 nm), whereas in CA, biglycan in the outer DIT can extract lipoproteins by direct contact with the blood. These facts lead to the single simplest explanation of all observations: (1) lipid deposition is initially localized in the outer DIT; (2) CA often develops at high blood LDL-C levels; (3) apparent CA can develop at lowered blood LDL-C levels. This mechanism is not unique to the coronary artery: for instance, the normally avascular cornea accumulates lipoproteins after neovascularization, resulting in lipid keratopathy.

Hypothesis

Neovascularization of the normally avascular coronary DIT by permeable vasculature from the adventitial vasa vasorum is the cause of LDL deposition and CA. DIT enlargement, seen in early CA and aging, causes hypoxia of the outer DIT and induces neovascularization. According to this alternative proposal, coronary atherosclerosis is not related to inflammation and can occur in individuals with normal circulating levels of LDL, consistent with research findings.

Background

Atherosclerosis, the predominant cause of coronary artery disease, remains enigmatic. Despite best efforts, available therapies protect only 30-40% of individuals at risk, and no therapeutic cure is anticipated for those who currently suffer from the disease. Delayed progress concerning pharmaceutical treatment implies that atherosclerosis drug development is in jeopardy, raising concerns among experts [1].

Logical properties and factual consistency concerning a currently endorsed hypothesis relating to coronary atherosclerosis: common perception of coronary artery morphology

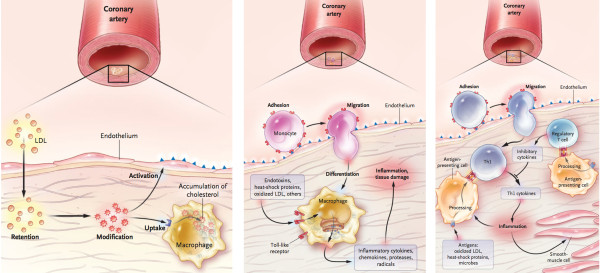

A currently endorsed hypothesis is based on the following assumptions: (1) atherosclerosis is a systemic disease, initiated by endothelial dysfunction due to (2) inflammation and (3) high levels of LDL, (4) leading to lipid and macrophage deposition in the tunica intima from blood of the coronary lumen, and plaque formation (modified response-to-injury hypothesis) [2,3]. This perception is presented in mainstream scientific publications and in educational materials, whether printed or electronic. This hypothesis is typically accompanied by familiar schematics depicting the pathogenesis of coronary atherosclerosis and transition from a normal cardiac artery to a diseased state, e.g. Figure 1

Analysis of main assumptions of the currently endorsed hypothesis

Assumption: atherosclerosis is a systemic disease

Factual contradiction

Atherosclerosis never affects the entire arterial bed; it is exclusive to large muscular arteries, particularly coronary, and to a lesser extent to elastic arteries. Therefore, this systemic notion should be rejected on logical grounds; atherosclerosis is NOT a systemic disease.

Assumption: atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease

Varieties of microorganisms are present in advanced atherosclerotic lesions, for example in specimens removed during atherectomy [7]. Fabricant et al. induced visible atherosclerotic changes in chicken coronary arteries resembling that in humans, by infecting them with herpesvirus [8-10] and suggested the viral role in pathogenesis, a view shared by many scientists (for review see [11,12]). Mycoplasma pneumonia or Chlamydia pneumoniae infections alone [13] or together with influenza virus [14] have been proposed as contributory factors in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, and particularly by participation in obstruction of vasa vasorum[11]. However, these cases probably do not indicate the initiation of atherosclerosis, but are more likely to represent secondary infection of degenerating/necrotic tissue. It should be emphasized that neither non-steroidal nor antibacterial anti-inflammatory treatments alter the risk of coronary atherosclerosis [15-18]. Despite the aforementioned studies [7-11,13,14], therefore, it can reasonably be claimed that no infectious cause of atherosclerosis has been demonstrated [19,20].

Assumption: a high level of LDL initiates and is the main cause of atherosclerosis

High levels of LDL are an important risk factor, and lowering LDL levels is the most significant pharmaceutical tool in coronary atherosclerosis prevention. However, the statement that high levels of LDL are the main cause of coronary atherosclerosis is inconsistent with established medical concepts.

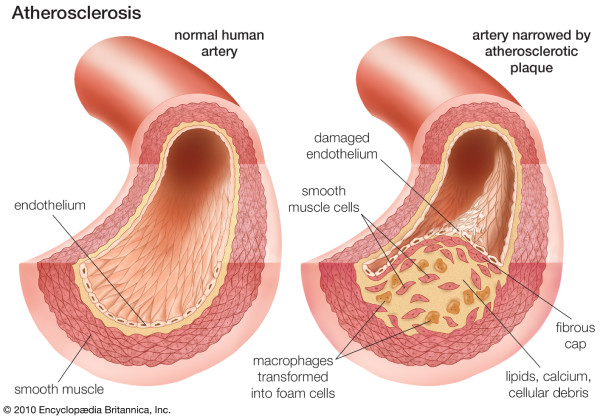

In addition to reporting significant findings on the precise location of lipid depositions during initiation of coronary atherosclerosis, this work univocally demonstrates that normal coronary tunica intima is not a single-layer endothelium covering a thin acellular compartment, as is commonly claimed in all mainstream scientific publications and educational materials (e.g. Figures 1 and 2), but a multi-layer cellular compartment where cells and matrix are arranged in a few dozen layers.

Coronary atherosclerosis. From: Atherosclerosis. Britannica Online Encyclopaedia. By courtesy of Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., copyright © 2010 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc; used with permission. [4].

Summary

(1) A hypotheses underlining our efforts to approach coronary atherosclerosis must be consistent with undisputed facts concerning the subject. Furthermore, a hypothesis should incorporate logical evaluation, and not contradict established and proven concepts in biology and medicine without well-grounded reasons.

(2) Atherosclerosis occurs in arteries with normal DIT, while sparing the rest of arterial bed. However, while normal DIT exists in numerous arteries [120,194], some of these are never affected by atherosclerosis; coronary arteries are almost always the target. On logical grounds, an arterial disease that never affects some arteries but usually affects certain others is not systemic.

(3) Coronary atherosclerosis is not an inflammatory disease, as multiple clinical trials demonstrate no correlation between anti-inflammatory therapies and risk of disease.

(4) High LDL levels are not a fundamental cause of coronary atherosclerosis, as lowering such levels protects only 30-40% of those at risk. Furthermore, humans and animals with normal LDL levels can suffer from coronary atherosclerosis.

(5) Neovascularization of the normally avascular DIT is the obligatory condition for coronary atherosclerosis development. This neovascularization originates from adventitial vasa vasorum and vascularizes the outer part of the coronary DIT, where LDL deposition initially occurs.

(6) It is suggested that excessive cell replication in DIT is a cause of DIT enlargement. Participation of enhanced matrix deposition is also plausible. An increase in DIT dimension impairs nutrient diffusion from the coronary lumen, causing ischemia of cells in the outer part of coronary DIT.

(7) Ischemia of the outer DIT induces angiogenesis and neovascularization from adventitial vasa vasorum. The newly formed vascular bed terminates in the outer part of the coronary DIT, above the internal elastic membrane, and consists of permeable vasculature.

(8) The outer part of the coronary DIT is rich in proteoglycan biglycan, which has a high binding capacity for LDL-C. While in avascular DIT, biglycan has very limited access to LDL-C due to diffusion distance and LDL-C properties; after neovascularization of the outer DIT, proteoglycan biglycan acquires access to LDL-C particles, and extracts and retains them.

(9) Initial lipoprotein influx and deposition occurs from the neovasculature originating from adventitial vasa vasorum – and not from the arterial lumen.

(10) Although lipoprotein deposition in the outer part of the coronary DIT is the earliest pathological manifestation of coronary atherosclerosis, intimal neovascularization from adventitial vasa vasorum must precede it.

Therefore, in the coronary artery tunica intima, a previously avascular tissue compartment becomes vascularized. All other tissue compartments are developed (both phylogenetically and ontogenetically) with constant exposure to capillary bed and blood, therefore their tissue components were selected not to bind LDL. This is why atherosclerosis is mostly limited to the coronary arteries. To my knowledge the only other example – the avascular cornea – shows the same lipid deposition after neovascularization.

The author does not claim that his hypothesis offers an immediate solution. Intimal cell proliferation, producing DIT and its later expansion, is cell hyperplasia, meaning that newly arrived cells are similar to normal residual cells, making systemic targeting very difficult. While the author strongly believes that intimal neovascularization is the crucial step in the pathogenesis of coronary atherosclerosis, there are obvious concerns about angiogenesis inhibition in a heart with an already jeopardized myocardial blood supply. The author does not intend to suggest an immediate solution. The goal was to evaluate the hypothesis and the perceptions that we exercise in approaching coronary atherosclerosis logically and factually, and to offer a more coherent model. Furthermore, the intent was to underline paradoxical observations that could provide new insights into mechanisms of the disease. Atherosclerotic plaque growth and rupture are not paradoxical but anticipated events. In contrast, initial lipid deposition in outer layers of DIT with no deposition in inner layers is a paradoxical observation, and requires an explanatory model that differs from the accepted one. However, to recognize the paradox, correct perception of the coronary artery structure, where pathology occurs, must not be distorted by incorrect illustrations and verbal descriptions. When we name or depict things incorrectly, often just for nosological reasons, the incorrect perception of events may persist in spite of growing knowledge, impeding our attempts to discover the truth.

References

- Fryburg DA, Vassileva MT. Atherosclerosis drug development in jeopardy: the need for predictive biomarkers of treatment response. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:1–5. 72cm76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore S. In: In Anderson’s Pathology. Volume 1. 10th edition. Damjanov I, Linder J, Louis St, Mosby Mo, editor. 1996. Vascular System. A. Blood vessels and lymphatics; pp. 1397–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. he pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Britannica E. Atherosclerosis. In Britannica Online Encyclopaedia Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dzau VJ, Braun-Dullaeus RC, Sedding DG. Vascular proliferation and atherosclerosis: new perspectives and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2002;8:1249–1256. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1249. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ott SJ, El Mokhtari NE, Musfeldt M. et al.Detection of diverse bacterial signatures in atherosclerotic lesions of patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2006;113:929–937. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.579979. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricant CG, Fabricant J. Atherosclerosis induced by infection with Marek’s disease herpesvirus in chickens. Am Heart J. 1999;138:S465–468. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(99)70276-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricant CG, Fabricant J, Litrenta MM. et al.Virus-induced atherosclerosis. J Exp Med. 1978;148:335–340. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.1.335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Minick CR, Fabricant CG, Fabricant J. et al.Atheroarteriosclerosis induced by infection with a herpesvirus. Am J Pathol. 1979;96:673–706. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravnskov U, McCully KS. Review and hypothesis: vulnerable plaque formation from obstruction of Vasa vasorum by homocysteinylated and oxidized lipoprotein aggregates complexed with microbial remnants and LDL autoantibodies. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2009;39:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovic M, Smiljanic K, Dobutovic B. et al.Human cytomegalovirus infection and atherothrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012;33:160–172. doi: 10.1007/s11239-011-0662-x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Damy SB, Higuchi ML, Timenetsky J. et al.Mycoplasma pneumoniae and/or Chlamydophila pneumoniae inoculation causing different aggravations in cholesterol-induced atherosclerosis in apoE KO male mice. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:194. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Birck MM, Pesonen E, Odermarsky M. et al.Infection-induced coronary dysfunction and systemic inflammation in piglets are dampened in hypercholesterolemic milieu. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H1595–1601. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01253.2010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Matchaba P, Gitton X, Krammer G. et al.Cardiovascular safety of lumiracoxib: a meta-analysis of all randomized controlled trials > or =1 week and up to 1 year in duration of patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther. 2005;27:1196–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.07.019. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH. et al.Antibiotic treatment of Chlamydia pneumoniae after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1646–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043528. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grayston JT, Kronmal RA, Jackson LA. et al.Azithromycin for the secondary prevention of coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1637–1645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043526. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Andraws R, Berger JS, Brown DL. Effects of antibiotic therapy on outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;293:2641–2647. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2641. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle LE. Chlamydia pneumoniae and atherosclerosis: the end? Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16:267–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson C, Alp NJ. Role of Chlamydia pneumoniae in atherosclerosis. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;114:509–531. doi: 10.1042/CS20070298. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C. An introduction to the study of experimental medicine. New York: Henry Schuman, Inc.; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens WE. The concept of cause in disease. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38:947–950. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90130-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P. The forgotten majority: unfinished business in cardiovascular risk reduction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lands B. Planning primary prevention of coronary disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2009;11:272–280. doi: 10.1007/s11883-009-0042-6. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011;473:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nature10146. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anitschkow N. Über die experimentelle atherosklerose der herzklappen. Virchows Arch. 1915;220:233–256. doi: 10.1007/BF01949104. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel WB, Castelli WP, Gordon T. Cholesterol in the prediction of atherosclerotic disease. New perspectives based on the Framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonimus. Consensus conference. Lowering blood cholesterol to prevent heart disease. JAMA. 1985;253:2080–2086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonimus. Lowering blood cholesterol to prevent heart disease. NIH consensus development conference statement. Nutr Rev. 1985;43:283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonimus. NIH Consensus Development Conference. Lowering blood cholesterol to prevent heart disease. Wis Med J. 1985;84:18–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst ND. NIH consensus development conference on lowering blood cholesterol to prevent heart disease: implications for dietitians. J Am Diet Assoc. 1985;85:586–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonimus. Lowering blood cholesterol to prevent heart disease. Natl Inst Health Consens Dev Conf Consens Statement. 1985;5:27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonimus. Consensus development summaries. Lowering blood cholesterol to prevent heart disease. National Institutes of Health. Conn Med. 1985;49:357–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis C. Hold the Eggs and Butter. TIME. 1984;123:62. [Google Scholar]

- LaRosa JC. Reduction of serum LDL-C levels: a relationship to clinical benefits. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2003;3:271–281. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200303040-00006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig W. Treating residual cardiovascular risk: will lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 inhibition live up to its promise? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1642–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.025. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson J, Kovanen PT. Shifting to new targets in pharmacological prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2009;20:361–362. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32833158ce. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mitka M. Cholesterol drug lowers LDL-C levels but again fails to show clinical benefit. JAMA. 2010;303:211–212. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1915. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biasillo G, Leo M, Della Bona R. et al.Inflammatory biomarkers and coronary heart disease: from bench to bedside and back. Intern Emerg Med. 2010;5:225–233. doi: 10.1007/s11739-010-0361-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thorogood M. Vegetarianism, coronary disease risk factors and coronary heart disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1994;5:17–21. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199402000-00004. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay S, Chaikoff IL. In: In Atherosclerosis and its origin. Sandler M, Bourne GH, editor. New York: Academic Press; 1963. Naturally occuring arteriosclerosis in animals: a comparison with experimentally induced lesions; pp. 349–437. [Google Scholar]

- Bohorquez F, Stout C. Arteriosclerosis in exotic mammals. Atherosclerosis. 1972;16:225–231. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(72)90056-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh KG. Arteriosclerosis in the African elephant. I. Intimal atherosclerosis and its possible causes. Atherosclerosis. 1972;16:307–335. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(72)90080-9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay S, Chaikoff IL, Gilmore JW. Arteriosclerosis in the dog. I. Spontaneous lesions in the aorta and the coronary arteries. AMA Arch Pathol. 1952;53:281–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson R, Symons C. Arteriosclerosis in wild animals in captivity. Proc R Soc Med. 1961;54:973. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson R, Symons C, Fiennes RN. Atherosclerosis: a comparative study. Br Med J. 1962;1:501–507. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5277.501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Landé KE, Sperry WM. Human atherosclerosis in relation to the cholesterol content of the blood serum. Arch Pathol. 1936;22:301–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens WE. The role of lipid in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Lancet. 1975;1:724–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens WE. The hypothetical epidemic of coronary heart disease and atherosclerosis. Med Hypotheses. 1995;45:449–454. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(95)90219-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens WE. Atherosclerosis: usage and misusage. J Intern Med. 1998;243:395–398. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00327.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens WE. Use and misuse of atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 1999;245:311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens WE. Coronary heart disease, hypercholesterolemia, and atherosclerosis. II. Misrepresented data. Exp Mol Pathol. 2001;70:120–139. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2000.2339. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens WE. Coronary heart disease, hypercholesterolemia, and atherosclerosis. I. False premises. Exp Mol Pathol. 2001;70:103–119. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2000.2340. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens WE. Hypothetical hypercholesterolaemia and atherosclerosis. Med Hypotheses. 2004;62:72–78. doi: 10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00267-6. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ravnskov U. An elevated serum cholesterol level is secondary, not causal, in coronary heart disease. Med Hypotheses. 1991;36:238–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(91)90140-T. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ravnskov U. The questionable role of saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids in cardiovascular disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:443–460. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00018-3. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ravnskov U. A hypothesis out-of-date. the diet-heart idea. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:1057–1063. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00504-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ravnskov U. The fallacies of the lipid hypothesis. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2008;42:236–239. doi: 10.1080/14017430801983082. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ravnskov U. Cholesterol was healthy in the end. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2009;100:90–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascitelli L, Pezzetta F, Goldstein MR. Why the overstated beneficial effects of statins do not resolve the cholesterol controversy. QJM. 2009;102:435–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuchi M, Watanabe J, Kumagai K. et al.Normal and oxidized low density lipoproteins accumulate deep in physiologically thickened intima of human coronary arteries. Lab Invest. 2002;82:1437–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima Y, Fujii H, Sumiyoshi S. et al.Early human atherosclerosis: accumulation of lipid and proteoglycans in intimal thickenings followed by macrophage infiltration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1159–1165. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.134080. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stary HC, Blankenhorn DH, Chandler AB. et al.A definition of the intima of human arteries and of its atherosclerosis-prone regions. A report from the committee on vascular lesions of the council on arteriosclerosis, american heart association. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12:120–134. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.12.1.120. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima T, Tashiro T. Early morphologic stage of human coronary atherosclerosis. Kurume Med J. 1968;15:235–242. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.15.235. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RT, Yamamoto C, Feng Y. et al.Mechanical strain induces specific changes in the synthesis and organization of proteoglycans by vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13847–13851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little PJ, Tannock L, Olin KL. et al.Proteoglycans synthesized by arterial smooth muscle cells in the presence of transforming growth factor-beta1 exhibit increased binding to LDLs. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:55–60. doi: 10.1161/hq0102.101100. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima Y, Wight TN, Sueishi K. Early atherosclerosis in humans: role of diffuse intimal thickening and extracellular matrix proteoglycans. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:14–23. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn099. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima Y, Chen YX, Kinukawa N. et al.Distributions of diffuse intimal thickening in human arteries: preferential expression in atherosclerosis-prone arteries from an early age. Virchows Arch. 2002;441:279–288. doi: 10.1007/s00428-002-0605-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Subbotin VM. Analysis of arterial intimal hyperplasia: review and hypothesis. Theor Biol Med Model. 2007;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-4-41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma R. Ueber die Abhängigkeit der Bindegewebsneubildung in der Arterienintima von den mechanischen Bedingungen des Blutumlaufes. Erste Mittheilung. Die Rückwirkung des Verschlusses der Nabelarterien und des arteriösen Ganges auf die Structur der Aortenwand. Archiv fur pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und fur klinische Medicin (Virchows Archiv) 1883;93:443–505. [Google Scholar]

- Stary HC, Blankenhorn DH, Chandler AB. et al.A definition of the intima of human arteries and of its atherosclerosis- prone regions. A report from the committee on vascular lesions of the council on arteriosclerosis, american heart association. Circulation. 1992;85:391–405. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.85.1.391. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkoff K. Über die histologische Struktur der Coronararterien des menschlichen Herzens. Virchows Arch. 1923;241:42–58. doi: 10.1007/BF01942462. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stary HC, Chandler AB, Glagov S. et al.A definition of initial, fatty streak, and intermediate lesions of atherosclerosis. A report from the committee on vascular lesions of the council on arteriosclerosis, american heart association. Circulation. 1994;89:2462–2478. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.89.5.2462. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha M, Leask RL, Butany J. et al.Distribution of intimal and medial thickening in the human right coronary artery: a study of 17 RCAs. Atherosclerosis. 2001;158:147–153. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(00)00759-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Seierstad SL, Svindland A, Larsen S. et al.Development of intimal thickening of coronary arteries over the lifetime of Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., fed different lipid sources. J Fish Dis. 2008;31:401–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2008.00913.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Houser S, Muniappan A, Allan J. et al.Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: real or a normal morphologic variant? J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.11.012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Nakazawa G. et al.Is pathologic intimal thickening the key to understanding early plaque progression in human atherosclerotic disease? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:986–989. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.0000258865.44774.41. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Burke AP, Farb A, Malcom GT. et al.Coronary risk factors and plaque morphology in men with coronary disease who died suddenly. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1276–1282. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705013361802. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stary HC. An atlas of atherosclerosis: progression and regression. New York: Parthenon Publishing Group; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kolodgie FD, Virmani R, Burke AP. et al.Pathologic assessment of the vulnerable human coronary plaque. Heart. 2004;90:1385–1391. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.041798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam N, Roman-Rego A, Ong P. et al.Atherosclerotic plaque regression: fact or fiction? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2010;24:311–317. doi: 10.1007/s10557-010-6241-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tabas I, Williams KJ, Boren J. Subendothelial lipoprotein retention as the initiating process in atherosclerosis: update and therapeutic implications. Circulation. 2007;116:1832–1844. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.676890. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- French JE. Atherosclerosis in relation to the structure and function of the arterial intima, with special reference to the endothelium. Int Rev Exp Pathol. 1966;5:253–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma R. Ueber die Abhangigkeit der Bindegewebsneubildung in der Arterienintima von den mechanischen Bedingungen des Blutumlaufes. Archiv fur pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und fur klinische Medicin (Virchows Archiv) 1886;105:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Thoma R. Über die intima der arterien. Virchows Arch. 1921;230:1–45. doi: 10.1007/BF01948742. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Consigny PM. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:553–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellmann HD. Textbook of Veterinary Histology. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ham AW. Histology. 9. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Junqueira LC, Carneiro J. Basic Histology : Text & Atlas. 11 International Edition. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DiCorleto PE, Gimbrone MAJ. In: In Atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease. 1. Fuster V, Ross R, Topol EJ, editor. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. Vascular Endothelium; pp. 387–399. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M. Pathogenesis of coronary artery disease. New York: Blakiston Division, McGraw-Hill; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg ID. In: In The Coronary Artery. Kalsner S, editor. New York: Oxford University Press; 1982. The endothelium: injury and repair of the arterial wall; pp. 417–432. [Google Scholar]

- Huttner I, Kocher O, Gabbani G. In: In Diseases of the arterial wall. Camilleri J-P, Berry CL, Fiessinger J-N, Bariety J, editor. London: Springer-Verlag; 1989. Endothelial and smooth-muscle cells; pp. 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehnel W. Color Atlas of Cytology, Histology, and Microscopic Anatomy. 4. New York: Thieme Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon RL, Niles NR. Medical histology : a text-atlas with introductory pathology. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ross MH, Kaye GI, Pawlina W. Histology : a text and atlas. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner LP, Hiatt JL. Color textbook of histology. 3. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal N, Xavier-Neto J. From the bottom of the heart: anteroposterior decisions in cardiac muscle differentiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:742–746. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00162-9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Medscape.com. [ http://www.medscape.com/]

- McPherson JA, Ahsan CH, Boudi FB. coronary artery atherosclerosis. In Medscape. 2011.

- Gallagher PJ. In: In Histology for Pathologists. 2. Sternberg SS, editor. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. Blood Vessels. Chapter 33; pp. 763–786. [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens WE. Vascular Pathology. London: Chapman & Hall Medical; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rader DJ, Daugherty A. Translating molecular discoveries into new therapies for atherosclerosis. Nature. 2008;451:904–913. doi: 10.1038/nature06796. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha VZ, Libby P. Obesity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:399–409. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.55. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anitschkow NN. In: In Cowdry’s arteriosclerosis; a survey of the problem. 2. Blumenthal HT, editor. Springfield, Ill: Thomas; 1967. A history of experimentation on arterial atherosclerosis in animals; pp. 22–44. [Google Scholar]

- Geiringer E. Intimal vascularization and atherosclerosis. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1951;63:201–211. doi: 10.1002/path.1700630204. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Torzewski M, Navarro B, Cheng F. et al.Investigation of Sudan IV staining areas in aortas of infants and children: possible prelesional stages of atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.01.038. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stary HC, Chandler AB, Glagov S. et al.A definition of initial, fatty streak, and intermediate lesions of atherosclerosis. A report from the committee on vascular lesions of the council on arteriosclerosis, american heart association. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:840–856. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.14.5.840. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Miyao Y, Kugiyama K, Kawano H. et al.Diffuse intimal thickening of coronary arteries in patients with coronary spastic angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:432–437. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00729-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Garvin MR, Labinaz M, Pels K. et al.Arterial expression of the plasminogen activator system early after cardiac transplantation. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35:241–249. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(97)00088-6. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Miller H, Poon S, Hibbert B. et al.Modulation of estrogen signaling by the novel interaction of heat shock protein 27, a biomarker for atherosclerosis, and estrogen receptor beta: mechanistic insight into the vascular effects of estrogens. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:e10–14. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000156536.89752.8e. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien ER, Bennett KL, Garvin MR. et al.Beta ig-h3, a transforming growth factor-beta-inducible gene, is overexpressed in atherosclerotic and restenotic human vascular lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:576–584. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.16.4.576. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JK, Heistad DD. Structure and function of vasa vasorum. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1996;6:53–57. doi: 10.1016/1050-1738(96)00008-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno PR, Purushothaman KR, Sirol M. et al.Neovascularization in human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2006;113:2245–2252. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.578955. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pels K, Labinaz M, O’Brien ER. Arterial wall neovascularization–potential role in atherosclerosis and restenosis. Jpn Circ J. 1997;61:893–904. doi: 10.1253/jcj.61.893. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson C, Southwood M, Pitman R. et al.Angiogenesis occurs within the intimal proliferation that characterizes transplant coronary artery vasculopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:551–558. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.03.012. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barr J. An Address On Arterio-Sclerosis. The British Medical Journa. 1905;1:53–57. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.2298.53. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Winternitz MC, Thomas RM, LeCompte PM. The Biology of Arteriosclerosis. Springfield, Ill: C. C. Thomas; 1938. [Google Scholar]

- LeCompte PM. In: In Cowdry’s arteriosclerosis; a survey of the problem. 2. Blumenthal HT, editor. Springfield, Ill: Thomas; 1967. Reactions of the vasa vasorum in vascular disease; pp. 212–224. [Google Scholar]

- Vink A, Schoneveld AH, Poppen M. et al.Morphometric and immunohistochemical characterization of the intimal layer throughout the arterial system of elderly humans. J Anat. 2002;200:97–103. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-8782.2001.00005.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wolinsky H, Glagov S. Nature of species differences in the medial distribution of aortic vasa vasorum in mammals. Circ Res. 1967;20:409–421. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.20.4.409. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sueishi K, Yonemitsu Y, Nakagawa K. et al.Atherosclerosis and angiogenesis. Its pathophysiological significance in humans as well as in an animal model induced by the gene transfer of vascular endothelial growth factor. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;811:311–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52011.x. 322–314. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heistad DD, Armstrong ML. Blood flow through vasa vasorum of coronary arteries in atherosclerotic monkeys. Arteriosclerosis. 1986;6:326–331. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.6.3.326. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann J, Lerman LO, Rodriguez-Porcel M. et al.Coronary vasa vasorum neovascularization precedes epicardial endothelial dysfunction in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;51:762–766. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00347-9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Cliff WJ, Schoefl GI. et al.Immunohistochemical study of intimal microvessels in coronary atherosclerosis. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:164–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisov DS, Kolocolchicova EG, Varava BN. et al.Morphogenesis of intimal thickening in nonspecific aortoarteritis. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:1048–1056. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90222-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto M, Nakashima Y, Sueishi K. Intimal neovascularization in human coronary atherosclerosis: its origin and pathophysiological significance. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:450–456. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90148-5. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt HA, Gossl M, Mannheim D. et al.Differential distribution of vasa vasorum in different vascular beds in humans. Atherosclerosis. 2008;199:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.09.015. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T, Nakashima Y, Yonemitsu Y. et al.Angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis and expression of lymphangiogenic factors in the atherosclerotic intima of human coronary arteries. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.01.001. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Regar E, van Beusekom HM, van der Giessen WJ. et al.Images in cardiovascular medicine. Optical coherence tomography findings at 5-year follow-up after coronary stent implantation. Circulation. 2005;112:e345–346. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.531897. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Sumiyoshi S, Nakashima Y. et al.Overexpression of heme oxygenase-1 in coronary atherosclerosis of Japanese autopsies with diabetes mellitus: Hisayama study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;202:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.057. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon HM, Sangiorgi G, Ritman EL. et al.Enhanced coronary vasa vasorum neovascularization in experimental hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1551–1556. doi: 10.1172/JCI1568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak HF, Brown LF, Detmar M. et al.Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor, microvascular hyperpermeability, and angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:1029–1039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JA, Benjamin L, Zeng H. et al.Vascular permeability, vascular hyperpermeability and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2008;11:109–119. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9099-z. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Babin PJ, Gibbons GF. The evolution of plasma cholesterol: Direct utility or a “spandrel” of hepatic lipid metabolism? Prog Lipid Res. 2009;48:73–91. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2008.11.002. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Levy FH, Kelly DP. Regulation of ATP synthase subunit e gene expression by hypoxia: cell differentiation stage-specific control. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C457–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliff WJ, Schoefl GI. Pathological vascularization of the coronary intima. Ciba Found Symp. 1983;100:207–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mause SF, Weber C. Intrusion through the fragile back door: immature plaque microvessels as entry portals for leukocytes and erythrocytes in atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1528–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.047. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sluimer JC, Kolodgie FD, Bijnens AP. et al.Thin-walled microvessels in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques show incomplete endothelial junctions relevance of compromised structural integrity for intraplaque microvascular leakage. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1517–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.056. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Takano M, Yamamoto M, Inami S. et al.Appearance of lipid-laden intima and neovascularization after implantation of bare-metal stents extended late-phase observation by intracoronary optical coherence tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;55:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.032. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ruben M. Corneal vascularization. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1981;21:27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar DT. Corneal angiogenic privilege: angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in corneal avascularity, vasculogenesis, and wound healing (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis) Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2006;104:264–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogan DC, Kuwabara T. Lipid keratopathy and atheroma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1958;56:109–119. discussion 109–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta D, Illingworth C. Treatments for corneal neovascularization: a review. Cornea. 2011;30:927–938. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318201405a. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RJ, Stulting RD, Hendricks RL. et al.Corneal neovascularization. Pathogenesis and inhibition. Cornea. 1987;6:250–257. doi: 10.1097/00003226-198706040-00004. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abdullah AA, Al-Assiri A. Resolution of bilateral corneal neovascularization and lipid keratopathy after photodynamic therapy with verteporfin. Optometry. 2011;82:212–214. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2010.09.012. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chu HS, Hu FR, Yang CM. et al.Subconjunctival injection of bevacizumab in the treatment of corneal neovascularization associated with lipid deposition. Cornea. 2011;30:60–66. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181e458c5. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung SN, Lichtinger A, Kim P. et al.Combined use of subconjunctival and intracorneal bevacizumab injection for corneal neovascularization. Cornea. 2011;30:1110–1114. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31821379aa. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler KU, Seifert P. Unusual idiopathic lipid keratopathy: a newly recognized entity? Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1435–1438. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.10.1435. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Duran JA, Rodriguez-Ares MT. Idiopathic lipid corneal degeneration. Cornea. 1991;10:166–169. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199103000-00013. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Arentsen JJ. Corneal neovascularization in contact lens wearers. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1986;26:15–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JY, Kim MK, Wee WR. Subconjunctival and intracorneal bevacizumab injection for corneal neovascularization in lipid keratopathy. Cornea. 2009;28:1070–1073. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31819839f9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peter J, Fraenkel G, Goggin M. et al.Fluorescein angiographic monitoring of corneal vascularization in lipid keratopathy. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2004;32:78–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2004.00764.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Araujo A, Tavares MA, Lemos MM. et al.Primary lipid keratopathy: a morphological and biochemical assessment. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:248–250. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.4.248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy C, Stock EL, Mendelsohn AD. et al.Pathogenesis of experimental lipid keratopathy: corneal and plasma lipids. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28:1492–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierczak Z, Pandzioch Z. Chromatographic identification of lipids from the aqueous eye humor. Microchem J. 1981;26:399–401. doi: 10.1016/0026-265X(81)90117-X. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Koutselinis A, Kalofoutis A, Boukis S. Major Lipid Classes in Aqueous-Humor after Death. Metab Ophthalmol. 1978;2:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kalofoutis A, Julien G, Boukis D. et al.Chemistry of Death.2. Phospholipid Composition of Aqueous-Humor after Death. Forensic Sci. 1977;9:229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olin DD, Rogers WA, Macmillan AD. Lipid-laden aqueous-humor associated with anterior uveitis and concurrent hyperlipemia in 2 dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1976;168:861–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Martens FW. Lipids in the aqueous humor of the cattle eye and their role as potential nutritive substrates for the cornea. Bericht uber die Zusammenkunft Deutsche Ophthalmologische Gesellschaft. 1972;71:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma SD, Reddy VN. Phospholipid Composition of Aqueous Humor, Plasma and Lens in Normal and Alloxan Diabetic Rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 1972;13:120-. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(72)90024-3. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Herring M, Smith J, Dalsing M. et al.Endothelial seeding of polytetrafluoroethylene femoral popliteal bypasses: the failure of low-density seeding to improve patency. J Vasc Surg. 1994;20:650–655. doi: 10.1016/0741-5214(94)90291-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen N, Lindblad B, Bergqvist D. Endothelial cell seeded dacron aortobifurcated grafts: platelet deposition and long-term follow-up. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1994;35:425–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. Recent progress in understanding atherosclerosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31:231–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt SP, Meerbaum SO, Anderson JM. et al.Evaluation of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene arteriovenous access grafts onto which microvessel-derived cells were transplanted to “improve” graft performance: preliminary results. Ann Vasc Surg. 1998;12:405–411. doi: 10.1007/s100169900176. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Walpoth BH, Pavlicek M, Celik B. et al.Prevention of neointimal proliferation by immunosuppression in synthetic vascular grafts. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:487–492. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(01)00582-6. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Walpoth BH, Rogulenko R, Tikhvinskaia E. et al.Improvement of patency rate in heparin-coated small synthetic vascular grafts. Circulation. 1998;98:II319–323. discussion II324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballermann BJ, Dardik A, Eng E. et al.Shear stress and the endothelium. Kidney Int Suppl. 1998;67:S100–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glagov S. Intimal hyperplasia, vascular modeling, and the restenosis problem. Circulation. 1994;89:2888–2891. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.89.6.2888. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gloe T, Sohn HY, Meininger GA. et al.Shear stress-induced release of basic fibroblast growth factor from endothelial cells is mediated by matrix interaction via integrin alpha(v)beta3. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23453–23458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203889200. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Karino T, Motomiya M, Goldsmith HL. Flow patterns at the major T-junctions of the dog descending aorta. J Biomech. 1990;23:537–548. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90047-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sho M, Sho E, Singh TM. et al.Subnormal shear stress-induced intimal thickening requires medial smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Exp Mol Pathol. 2002;72:150–160. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2002.2426. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sunamura M, Ishibashi H, Karino T. Flow patterns and preferred sites of intimal thickening in diameter-mismatched vein graft interpositions. Surgery. 2007;141:764–776. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.12.019. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Riha GM, Yan S. et al.Shear stress induces endothelial differentiation from a murine embryonic mesenchymal progenitor cell line. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1817–1823. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000175840.90510.a8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Lee S, Singh TM. et al.Molecular mechanisms of aortic wall remodeling in response to hypertension. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:570–578. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.112231. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Sokabe T, Watabe T. et al.Fluid shear stress induces differentiation of Flk-1-positive embryonic stem cells into vascular endothelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1915–1924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Takahashi T, Asahara T. et al.Proliferation, differentiation, and tube formation by endothelial progenitor cells in response to shear stress. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:2081–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi M, Takahashi M, Kobayashi M. et al.Normalization of high-flow or removal of flow cannot stop high-flow induced endothelial proliferation. Biomed Res. 2005;26:21–28. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.26.21. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Subbotin V. In: In New Approaches in Coronary Artery Disease 8th International Congress on Coronary Artery Disease; October 11–14, 2009; Prague, Czech Republic. Lewis BL, Widimsky P, Flugelman MY, Halon DA, Medimond , editor. 2009. Arterial intimal hyperplasia: biological analysis of the disease and possible approaches to the problem; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Milewicz DM, Kwartler CS, Papke CL. et al.Genetic variants promoting smooth muscle cell proliferation can result in diffuse and diverse vascular diseases: evidence for a hyperplastic vasculomyopathy. Genet Med. 2010;12:196–203. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181cdd687. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- French JE, Jennings MA, Poole JCF. et al.Intimal Changes in the Arteries of Ageing Swine. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1963;158:24–42. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1963.0032. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf N. Pathology of Atherosclerosis. London Butterworth Scientific; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn GR. The incubation period of coronary thrombosis; with a chapter on haemodynamics of the coronary circulation by R. F. Davis. London: Butterworths; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Marti HJ, Bernaudin M, Bellail A. et al.Hypoxia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression precedes neovascularization after cerebral ischemia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:965–976. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64964-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. Regulation of vascularization by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1177:2–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05032.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hauss WH, Junge-Huelsing G, Hollander HJ. Changes in metabolism of connective tissue associated with ageing and arterio- or atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Res. 1962;2:50–61. doi: 10.1016/S0368-1319(62)80052-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anonimus. REPORT of committee on nomenclature of the american society for the study of arteriosclerosis; tentative classification of arteriopathies. Circulation. 1955;12:1065–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymus. (Department of Health EaWNIoH ed., vol. 2. DHED Publication No. (NIH); 1971. Atherosclerosis: a report by the National Heart and Lung Institute Task Force on Atherosclerosis. pp. 72–219. [Google Scholar]

- Moschcowitz E. Hyperplastic arteriosclerosis versus atherosclerosis. J Am Med Assoc. 1950;143:861–865. doi: 10.1001/jama.1950.02910450001001. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro WD. Coronary disease in the young. Dissertation. University of Wisconsin, Medicine; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens WE. In: In Vascular Pathology. Stehbens WE, Lie JT, editor. London: Chapman & Hall Medical; 1995. Atherosclerosis and Degerative Diseases of Blood Vessels; pp. 175–269. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WA, Kim DN. Biology of disease. Atherosclerosis as a hyperplastic and/or neoplastic process. Lab Invest. 1983;48:245–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis–an update. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:488–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198602203140806. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein GA, Fishbein MC. Arteriosclerosis: rethinking the current classification. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1309–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]