Role of Body Mass Index in Acute Kidney Injury Patients after Cardiac Surgery

Zhouping Zou,a Yamin Zhuang,b Lan Liu,b Bo Shen,a,c,d Jiarui Xu,a,c,d Zhe Luo,b Jie Teng,a,c,d,e,* Chunsheng Wang,b and Xiaoqiang Dinga,c,d

Abstract

Background/Aims

To explore the association of body mass index (BMI) with the risk of developing acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery (CS-AKI) and for AKI requiring renal replacement therapy (AKI-RRT) after cardiac surgery.

Methods

Clinical data of 8,455 patients undergoing cardiac surgery, including demographic preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative data were collected. Patients were divided into underweight (BMI <18.5), normal weight (18.5≤ BMI <24), overweight (24≤ BMI <28), and obese (BMI ≥28) groups. The influence of BMI on CS-AKI incidence, duration of hospital, and intensive care unit (ICU) stays as well as AKI-related mortality was analyzed.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 53.2 ± 13.9 years. The overall CS-AKI incidence was 33.8% (n = 2,855) with a hospital mortality of 5.4% (n = 154). The incidence of AKI-RRT was 5.2% (n = 148) with a mortality of 54.1% (n = 80). For underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese cardiac surgery patients, the AKI incidences were 29.9, 31.0, 36.5, and 46.0%, respectively (p < 0.001). The hospital mortality of AKI patients in the 4 groups was 9.5, 6.0, 3.8, and 4.3%, whereas the hospital mortality of AKI-RRT patients in the 4 groups was 69.2, 60.8, 36.4, and 58.8%, both significantly different (p < 0.05). Hospital and ICU stay durations were not significantly different in the 4 BMI groups.

Conclusion

The hospital prognosis of AKI and AKI-RRT patients after cardiac surgery was best when their BMI was in the 24–28 range.Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Body mass index, Cardiac surgery, Hospital mortality, Renal replacement therapy

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common and serious complication of cardiac surgery; AKI has been reported to occur in 5–50% of hospitalized patients undergoing cardiac surgery based on different definitions of AKI [1, 2, 3]. AKI after cardiac surgery (CS-AKI) patients have higher mortality rates than those who did not develop AKI [4, 5], and the mortality rate of AKI-renal replacement therapy (AKI-RRT) patients has been reported to be 41.4–65% [6, 7, 8, 9]. Current research has found that there are many factors related to the incidence of CS-AKI and its outcome, with body mass index (BMI) being one of these risk factors. Obesity and high BMI have recently been demonstrated to be associated with AKI in intensive care units and postsurgical populations [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Few studies have focused on the role of BMI in the incidence and prognosis of CS-AKI in China; therefore, the relationship between BMI and AKI in China remains unclear. In addition, BMI classification standards, primary diseases, and complications are differently defined in Caucasian patients, and related foreign research may not be completely applicable to the Chinese.

In the present study, BMI classification was carried out following the standards established for the Chinese population in order to understand the impact of BMI on CS-AKI in Chinese people and provide prevention and control strategies in Asians.

Patients and Methods

Study Population

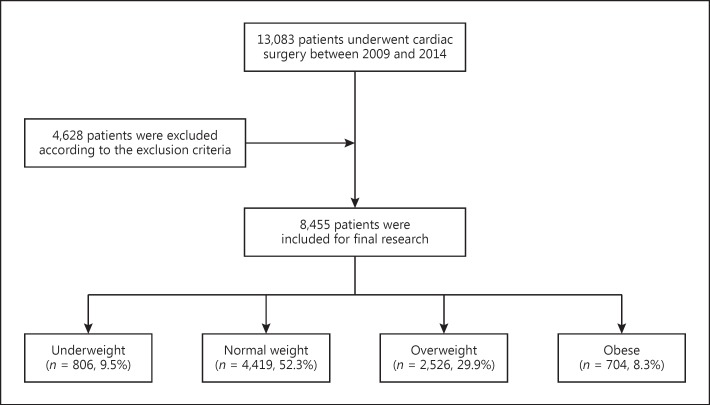

This was a retrospective study of patients who underwent valve and cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) cardiac surgery between January 2009 and December 2014 in the Zhongshan Hospital affiliated to Fudan University. The Ethical Committee of Zhongshan Hospital approved the study, and all participating patients gave their informed consent. A total of 8,455 eligible adult patients were included. The exclusion criteria were: patients ≤18 years old; solitary kidney or history of kidney transplants; undergoing cardiac transplantation; preoperative circulatory assist devices; patients who had preoperative RRT; or a lack of clinical data (Fig. (Fig.11).

Flowchart of the present study.

AKI and BMI Definitions

AKI was defined according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) [15, 16] criteria: (1) increase in serum creatinine (SCr) by ≥0.3 mg/dL (≥26.5 μmol/L) within 48 h; (2) increase in SCr to ≥1.5 times baseline, which is known or presumed to have occurred within the prior 7 days; (3) urine volume <0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 h and was staged according to the SCr and urine output.

The BMI classification (BMI = weight [kg]/height [m2]) followed the standards established for the Chinese according to the Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health [17], and the patients were divided into 4 groups: underweight group (BMI <18.5); normal-weight group (18.5≤ BMI <24); overweight group (24≤ BMI <28); and obese group (BMI ≥28).

Clinical Trial Design and Methods

The clinical data including preoperative as well as intraoperative and postoperative variables of patients were recorded. Preoperative data included baseline characteristics, complications, preoperative renal function (defined as the latest available SCr value prior to cardiac surgery), and perioperative cardiac functions (classification by NYHA [18]). Intraoperative variables included cardiac output data from echocardiography, duration of CPB time in minutes, aortic cross-clamp times, and type of surgery. Postoperative variables included duration of mechanical ventilation, urine output in the first 24 h after cardiac surgery, incidence and stage of AKI as well as hospital mortality of AKI and AKI-RRT patients.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause hospital mortality. The secondary outcome was length of stay in the ICU and hospital.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, (version 20.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). AKI Incidence was compared among the BMI groups using the Pearson χ2 test. Demographic, preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables were compared among the BMI groups using a one-way ANOVA test for the continuous variables and the Pearson χ2 test for the categorical variables. The association of the demographic, preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables with AKI was tested using a two-sample t test or a Wilcoxon rank-sum test for the continuous variables and the Pearson χ2 test for the categorical variables. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables, and as frequency counts (%) for the categorical variables. Two-tailed p values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

A total of 8,455 patients were enrolled, of which 4,706 (55.7%) were male and 3,749 (44.3%) were female. The mean age was 53.2 ± 13.9 years, and the mean BMI 23.0 ± 3.6. The distribution of patients by BMI group was 806 (9.5%) in the underweight group, 4,419 (52.3%) in the normal weight group, 2,526 (29.9%) in the overweight group, and 704 (8.3%) in the obese group. The mean age, proportion of males, baseline SCr, proportions of hypertension, diabetes, coronary angiography, chronic heart failure (NYHA >II), and baseline uric acid were increased with increasing BMI (Table (Table11).

Table 1

Comparison of baseline characteristics among the four BMI groups

| Underweight (n = 806) | Normal weight (n = 4,419) | Overweight (n = 2,526) | Obese (n = 704) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, % | 340 (42.2) | 2,251 (51.0) | 1,644 (65.1) | 471 (66.9) | <0.001 |

| Age, years | 47.8 ± 16.6 | 52.6 ±14.1 | 55.3 ± 12.2 | 55.0 ± 11.9 | <0.001 |

| Height, cm | 163.6 ± 7.3 | 163.4 ±7.2 | 166.4 ± 7.0 | 166.1 ± 8.0 | <0.001 |

| Body weight, kg | 46.0 ± 5.2 | 58.0 ±6.6 | 71.2 ± 6.8 | 83.0 ± 8.2 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 97 (12.0) | 1,042 (23.6) | 922 (36.5) | 344 (48.9) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % NYHA | 38 (4.7) | 292 (6.6) | 307 (12.2) | 111 (15.8) | <0.001 |

| I–II | 313 (38.8) | 1,890 (42.8) | 1,130 (44.7) | 300 (42.6) | 0.030 |

| III–IV | 493 (61.2) | 2,529 (57.2) | 1,396 (55.3) | 404 (57.4) | 0.030 |

| Preoperative LVEF, % | 62.1 ± 9.2 | 61.8 ±9.2 | 62.1 ± 8.5 | 61.5 ± 9.3 | 0.710 |

| CPB time, min | 93.9 ± 44.6 | 93.6 ±37.8 | 98.1 ± 38.0 | 100.4 ± 42.4 | <0.001 |

| ACC time, min | 54.9 ± 25.7 | 56.1 ±26.8 | 58.2 ± 25.9 | 57.3 ± 26.5 | 0.009 |

| Preoperative coronary angiography n, % | 206 (25.6) | 1,524 (34.5) | 1,090 (43.2) | 304 (43.2) | <0.001 |

| Interval between coronary angiography and cardiac surgery, days | 3 (2.5) | 3 (2.6) | 4 (2.6) | 4 (2.6) | 0.048 |

| Albumin baseline, g/L | 39.8 ± 4.1 | 40.2 ±3.6 | 40.3 ± 3.3 | 40.4 ± 3.1 | 0.014 |

| UA baseline, µmol/L | 342.0 ± 114.6 | 354.7 ±117.4 | 377.8 ± 141.8 | 396.0 ± 109.5 | <0.001 |

| eGFR baseline, mL/min | 98.2 ± 28.6 | 91.9 ±25.1 | 89.3 ± 23.1 | 87.3 ± 23.1 | <0.001 |

| SCr baseline, µmol/L | 73.4 ± 25.0 | 77.4 ±25.3 | 80.9 ± 24.0 | 83.0 ± 24.4 | <0.001 |

| BUN baseline, mmol/L | 6.6 ± 3.0 | 6.6 ±2.9 | 6.3 ± 2.2 | 6.3 ± 2.0 | 0.005 |

NYHA, New York Heart Association; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; ACC aortic cross-clamp; UA, uric acid; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; SCr, serum creatinine; BUN, blood urea nitrogen.

The Relationship between BMI and AKI Incidence

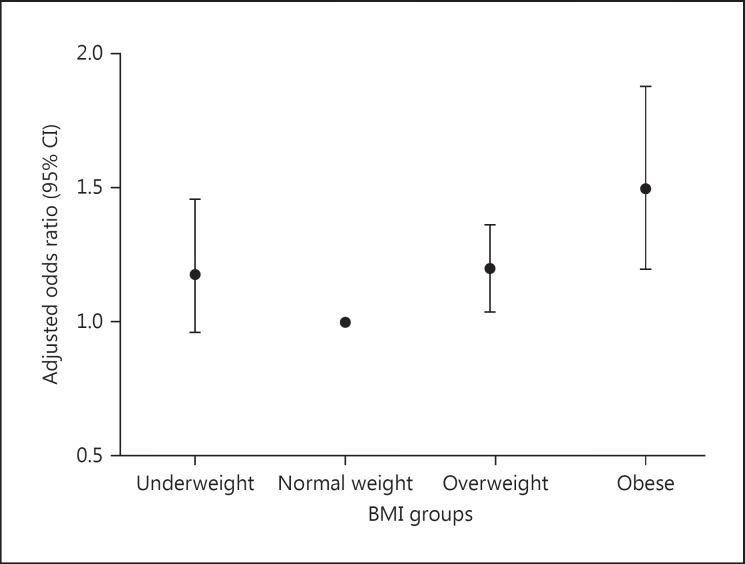

The overall incidence of CS-AKI was 33.8% (2,855/8,455). The AKI incidences were 29.9, 31.0, 36.5, and 46.0% in the underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese groups, respectively (p < 0.001). Each increment of 5 in admission BMI was associated with a 5.8% (95% CI, 4.2–7.4%; p < 0.001) higher adjusted risk of AKI according to the AKI diagnosis criteria of KDIGO. The incidence of AKI stage 2 and 3 was 33.2, 26.2, 27.7, and 31.2% in the 4 groups, respectively (p = 0.067) (Table (Table2).2). The adjusted odds ratios of AKI were 1.18 (95% CI, 0.96–1.46), 1.20 (1.04–1.37), and 1.50 (1.20–1.88) when underweight, overweight, and obesity groups were compared with the normal-weight group (Fig. (Fig.22).

Adjusted odds ratios for the incidence of AKI in the respective BMI groups.

Table 2

Incidence of AKI after cardiac surgery among the four groups

| Underweight | Normal weight | Overweight | Obese | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKI, n (%) | 241 (29.9) | 1,368 (31.0) | 922 (36.5) | 324 (46.0) | <0.001 |

| AKI stage 1, n (%) | 161 (66.8) | 1,010 (73.8) | 667 (72.3) | 223 (68.8) | 0.067 |

| AKI stage 2 n (%) | 51 (21.2) | 205 (15.0) | 154 (16.7) | 67 (20.7) | 0.018 |

| AKI stage 3, n (%) | 29 (12.0) | 153 (11.2) | 101 (11.0) | 34 (10.5) | 0.948 |

| AKI stage 2 – 3, n (%) | 80 (33.2) | 358 (26.2) | 255 (27.7) | 101 (31.2) | 0.067 |

AKI, acute kidney injury.

Obese patients had a significantly greater risk of developing AKI than those in the lower BMI groups. The odds ratio of CS-AKI in obese patients relative to the lower BMI groups was 1.39 (95% CI, 1.12–1.72; p < 0.001), even after accounting for covariates (i.e., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, age, heart function, preoperative albumin, preoperative SCr, and CPB time). According to the RIFLE standard, in which eGFR elevation or decline greater than or equal to 25% are set as a diagnostic criteria of AKI, the AKI incidences were 36.5% (294/806), 32.9% (1,454/4,419), 35.3% (892/2,526), and 42.5% (299/704) in the 4 groups, respectively (p < 0.001). Compared with KDIGO, when using RIFLE criteria, the AKI incidences from normal BMI to obese patients group all increased, while the AKI incidence rate in the underweight group was enhanced compared to normal-weight patients.

Risk Factors for the Development of CS-AKI

Next, we analyzed risk factors for CS-AKI in a univariate logistic regression model, and the results are presented in Table Table3.3. Apart from BMI and combined valve and CPB surgery, in particular gender (male), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, CHF, and CPB and aortic cross-clamp times were risk factors for developing CS-AKI (Table (Table33).

Table 3

Univariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for CS-AKI

| OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.031 | 1.027 – 1.035 | <0.001 |

| Gender (male) | 1.910 | 1.740 – 2.097 | <0.001 |

| BMI (additional BMI 5) | 1.282 | 1.210 – 1.359 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.704 | 1.546 – 1.879 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.444 | 1.239 – 1.683 | <0.001 |

| CHF (NYHA >II) | 1.475 | 1.345 – 1.618 | <0.001 |

| Preoperative coronary angiography | 1.429 | 1.303 – 1.568 | <0.001 |

| Albumin baseline | 0.955 | 0.942 – 0.968 | <0.001 |

| BUN baseline | 1.174 | 1.145 – 1.190 | <0.001 |

| SCr baseline | 1.014 | 1.012 – 1.016 | <0.001 |

| eGFR baseline | 0.990 | 0.988 – 0.992 | 0.035 |

| UA baseline | 1.003 | 1.003 – 1.004 | <0.001 |

| CPB additional 30 min | 1.487 | 1.425 – 1.551 | <0.001 |

| ACC additional 20 min | 1.263 | 1.215 – 1.313 | <0.001 |

| Valve surgery | 0.762 | 0.686 – 0.846 | <0.001 |

| CPB surgery | 1.040 | 0.929 – 1.164 | 0.498 |

| CPB + valve surgery | 3.024 | 2.407 – 3.801 | <0.0001 |

BMI, body mass index; CHF, chronic heart failure; NYHA, New York Heart Association; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; SCr, serum creatinine; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; UA, uric acid; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; ACC aortic cross-clamp.

The odds ratios of CS-AKI for the independent risk factors that were computed from the multivariate logistic regression model are shown in Table Table44.

Table 4

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for CS-AKI

| OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.037 | 1.031 – 1.043 | <0.001 |

| Gender (male) | 1.837 | 1.615 – 2.090 | <0.001 |

| BMI (additional BMI 5) | 1.155 | 1.058 – 1.260 | 0.001 |

| CHF (NYHA >II) | 1.216 | 1.064 – 1.390 | 0.004 |

| CPB (additional 30 min) | 1.410 | 1.334 – 1.491 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.156 | 1.001 – 1.325 | 0.048 |

| BUN baseline | 1.057 | 1.027 – 1.088 | <0.001 |

| UA baseline | 1.002 | 1.001 – 1.002 | <0.001 |

| Valve surgery | 0.826 | 0.619 – 1.102 | 0.194 |

| CPB surgery | 0.652 | 0.367 – 0.774 | 0.070 |

| CPB + valve surgery | 1.033 | 0.975 – 1.094 | 0.270 |

| SCr baseline | 0.999 | 0.995 – 1.002 | 0.491 |

BMI, body mass index; CHF, chronic heart failure; NYHA, New York Heart Association; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; UA, uric acid; SCr, serum creatinine.

Relationship between BMI and Prognosis of AKI

The overall incidence of AKI-RRT was 5.2% (148/2,855), with the incidence of AKI-RRT being 5.4, 5.4, 4.8, and 5.2% in underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese patients, respectively (p = 0.922). The mortality rate of AKI and AKI-RRT patients was 5.4% (154/2,855) and 54.1% (80/148), respectively. There were significant differences in mortality from AKI in underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity patients (9.5, 6.0, 3.8, and 4.3%, respectively; p = 0.002), and the adjusted odds ratios of mortality from AKI were 1.89 (95% CI, 1.50–3.41), 0.85 (95% CI, 0.52–1.39), and 0.95 (95% CI, 0.44–2.02) when underweight, overweight, and obese patients were compared with the normal weight group, respectively. There was also a significant difference in the mortality of AKI-RRT patients between the 4 BMI groups (69.2, 60.8, 36.4, and 58.8%, p = 0.041). The mortality of the underweight group was greatly increased when SCr levels were elevated to ≥106.4 μmol/L and eGFR declined by more than 60% compared with values before cardiac surgery. Comparisons of the duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU and hospital stay showed no significant differences for AKI or AKI-RRT patients among the 4 BMI groups (p > 0.05) (Table (Table55).

Table 5

The short-term prognosis of AKI and AKI-RRT after cardiac surgery among underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese patients

| Underweight | Normal weight | Overweight | Obese | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKI mortality, n (%) | 23/241 (9.5) | 82/1,368 (6.0) | 35/922 (3.8) | 14/324 (4.3) | 0.002 |

| Incidence of AKI-RRT, n (%) | 13/241 (5.4) | 74/1,368 (5.4) | 44/922 (4.8) | 17/324 (5.2) | 0.922 |

| AKI-RRT mortality, n (%) | 9/13 (69.2) | 45/74 (60.8) | 16/44 (36.4) | 10/17 (58.8) | 0.041 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, days | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 0.158 |

| LOS in ICU, h | 44 (20, 95) | 40 (20, 88) | 39 (20, 86) | 40 (19, 93) | 0.398 |

| LOS in hospital, days | 14 (10, 18) | 13 (10, 18) | 14 (11, 18) | 14 (11, 18) | 0.272 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; AKI-RRT, acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement; LOS, length of stay; ICU, intensive care unit.

Discussion

The overall CS-AKI incidence was 33.8%, which is in accordance with a previously published Chinese frequency of 31.2% [19]. The mortality rates of AKI and AKI-RRT patients were 5.4 and 54.1%, which is also in agreement with previously published rates of 4% for all CS-AKI patients [20] and 50% for CS-AKI-RRT patients [6] in non-Chinese studies. The present research has shown that increasing BMI, especially obesity (BMI ≥28), was associated with an increased incidence of AKI after cardiac surgery, which is in good agreement with previous literature. Billings et al. [14] studied the relationship between BMI and AKI incidence in 445 patients undergoing cardiac surgery, and reported that a higher BMI was associated with independently increased odds of AKI incidence (26.5% increase per 5 kg/m2; p = 0.02). A single-center retrospective study by Kumar et al. [21] classified the BMI of patients undergoing cardiac surgery after CPB into normal, overweight obesity class I, obesity class II, and obesity class III, based on the NIH definition for overweight and obesity. The results showed that among the BMI groups, the obese cohort (BMI >40) had a significantly higher risk of developing AKI after CPB than those in the lower BMI classes. BMI >40 was significantly associated with development of AKI even after accounting for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, age, the severity of the illness and CPB time (overall p = 0.018). The odds ratio of AKI after CPB in the BMI >40 cohort relative to BMI <25 patients was 2.39 (p = 0.055), with no significant difference in the risk of developing AKI after CPB among the 4 lower BMI classes. Since renal ischemia and reperfusion contribute to the development and progression of AKI [6], the factors related to obesity may cumulatively account for the increased risk of AKI after CPB in obese patients. The possible pathophysiological mechanisms may be that adipose tissue coupled with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia in obese patients leads to inappropriate activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis and increased oxidative stress in the kidneys by secreted hormones and cytokines [21, 22, 23, 24, 25]. In addition, obese patients have elevations in both kidney plasma flow and glomerular filtration rates, thereby promoting glomerular capillary hypertension, underlying occult and declared structural changes in the kidneys of obese patients [24]. However, our results revealed that although the incidence of AKI correlated with BMI, the mortality of AKI and AKI-RRT patients did not, being lowest in overweight patients and in agreement with previous studies, in which a high BMI had a survival benefit for AKI [13], CS-AKI [26], and cardiac surgery [27] patients. A recent Chinese study about the impact of BMI on the prognosis of AKI in geriatric postoperative major surgery patients revealed that elderly AKI patients of normal weight had a lower mortality risk compared to those who were underweight or obese [28]. Other researchers reported associations between mild obesity and hospital mortality after vascular surgery. This phenomenon is referred to as “reverse” or “paradox” epidemiology or “the obesity paradox” [29]. Also for RRT patients, U-shaped mortality rates have been reported [30], which is in accordance with our findings about AKI-RRT mortality and has been previously noted, particularly the mortality rates of Asian American end-stage renal disease patients [31]. However, AKI mortality in our study followed a reversed J shape, indicating that although obese people had an increased mortality risk compared to overweigh patients, their mortality incidence was still lower than for underweight and normal-weight cases, which is similar to the results from a previous report about mortality in nondialyzed advanced chronic kidney disease male patients [32]. The data indicated that in contrast to RRT, obesity was a survival advantage for AKI patients, which supports findings of Sleeman et al. [33], according to which obesity had beneficial effects on kidneys by inducing renal inflammation in a CPB swine model.

A multivariate analysis revealed that age, gender (male), CHF (NYHA >II), CPB, and hypertension were other risk factors besides BMI for developing AKI in cardiovascular surgery patients, which is in agreement with previous studies [19, 34].

It is striking that there were differences in the AKI incidence rates in the BMI groups calculated based on the RIFLE (GFR decline) and KDIGO (creatinine increase) criteria, which is probably related to the muscle mass in these patients, and further studies are warranted to determine unequivocally which method for AKI diagnosis is most suitable for Chinese patients.

One strength of our analysis was that we included a large number of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, and the BMI classification followed the standard established for Chinese patients, thereby considering representative data in Chinese hospitals. However, one limitation of the study is that there are no obesity-specific anthropometric measurement guidelines for Asians, such as abdominal circumference, waist-to-hip ratios, quantification of visceral fat mass and others. BMI as a measure of adiposity might also have inherent limitations, because BMI cannot identify differences in body composition and distribution of body fat, and BMI also does not quantify visceral adipose tissue, which may be the cornerstone in obesity-related pathophysiological processes. In addition, this was a single-center study and the known inherent limitations of this type of analysis apply to the present study.

In summary, the overall CS-AKI incidence was 33.8%, and the mortality rates of AKI and AKI-RRT cases were 5.4 and 54.1%. With increasing BMI, the overall incidence of CS-AKI increased significantly, but the mortality rates were lower in overweight and obese patients than in normal and underweight patients. There were no significant differences in the duration of mechanical ventilation, length of ICU, and hospital stay among the 4 BMI groups. A multivariate analysis revealed that age, gender (male), CHF (NYHA >II), CPB, and hypertension were other risk factors besides BMI for the development of AKI in cardiovascular surgery patients.

Statement of Ethics

All subjects have given their written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Zhongshan Hospital.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by The Project of Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (grant 2013SY048); The Project of Shanghai Municipal Commission of Science and Technology (grant 14DZ2260200); The Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau (grant 20134462).

References

1. Arora P, Kolli H, Nainani N, Nader N, Lohr J. Preventable risk factors for acute kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2012;26:687–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]2. Hobson CE, Yavas S, Segal MS, Schold JD, Tribble CG, Layon AJ, Bihorac A. Acute kidney injury is associated with increased long-term mortality after cardiothoracic surgery. Circulation. 2009;119:2444–2453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]3. Lagny MG, Jouret F, Koch JN, Blaffart F, Donneau AF, Albert A, Roediger L, Krzesinski JM, Defraigne JO. Incidence and outcomes of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery using either criteria of the RIFLE classification. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]4. Xu JR, Zhu JM, Jiang J, Ding XQ, Fang Y, Shen B, Liu ZH, Zou JZ, Liu L, Wang CS, Ronco C, Liu H, Teng J. Risk factors for long-term mortality and progressive chronic kidney disease associated with acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e2025. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]5. Shi Q, Hong L, Mu X, Zhang C, Chen X. Meta-analysis for outcomes of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e5558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]6. O’Neal JB, Shaw AD, Billings FTt. Acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery: current understanding and future directions. Crit Care. 2016;20:187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]7. Chertow GM, Lazarus JM, Christiansen CL, Cook EF, Hammermeister KE, Grover F, Daley J. Preoperative renal risk stratification. Circulation. 1997;95:878–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]8. Xu J, Shen B, Fang Y, Liu Z, Zou J, Liu L, Wang C, Ding X, Teng J. Postoperative fluid overload is a useful predictor of the short-term outcome of renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]9. Xu J, Ding X, Fang Y, Shen B, Liu Z, Zou J, Liu L, Wang C, Teng J. New, goal-directed approach to renal replacement therapy improves acute kidney injury treatment after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;9:103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]10. Thakar CV, Kharat V, Blanck S, Leonard AC. Acute kidney injury after gastric bypass surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:426–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]11. Praga M, Hernandez E, Herrero JC, Morales E, Revilla Y, Diaz-Gonzalez R, Rodicio JL. Influence of obesity on the appearance of proteinuria and renal insufficiency after unilateral nephrectomy. Kidney Int. 2000;58:2111–2118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]12. Glance LG, Wissler R, Mukamel DB, Li Y, Diachun CA, Salloum R, Fleming FJ, Dick AW. Perioperative outcomes among patients with the modified metabolic syndrome who are undergoing noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:859–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]13. Druml W, Metnitz B, Schaden E, Bauer P, Metnitz PG. Impact of body mass on incidence and prognosis of acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1221–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]14. Billings FT, 4th, Pretorius M, Schildcrout JS, Mercaldo ND, Byrne JG, Ikizler TA, Brown NJ. Obesity and oxidative stress predict AKI after cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1221–1228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]15. Kidney Disease. Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group: KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138. [Google Scholar]16. Jiang W, Teng J, Xu J, Shen B, Wang Y, Fang Y, Zou Z, Jin J, Zhuang Y, Liu L, Luo Z, Wang C, Ding X. Dynamic predictive scores for cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]17. Chen C, Lu FC, Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health PRC The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. 2004;17((suppl)):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]18. New York Heart Association . Nomenclature and Criteria for Diagnosis of Diseases of the Heart and Great Vessels. ed 9. Boston: Little, Brown & Co; 1994. pp. 253–256. [Google Scholar]19. Xu JR, Teng J, Fang Y, Shen B, Liu ZH, Xu SW, Zou JZ, Liu L, Wang CS, Ding XQ. The risk factors and prognosis of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a prospective cohort study of 4,007 cases (in Chinese) Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2012;51:943–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]20. Nafiu OO, Kheterpal S, Moulding R, Picton P, Tremper KK, Campbell DA, Jr, Eliason JL, Stanley JC. The association of body mass index to postoperative outcomes in elderly vascular surgery patients: a reverse J-curve phenomenon. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]21. Kumar AB, Bridget Zimmerman M, Suneja M. Obesity and post-cardiopulmonary bypass-associated acute kidney injury: a single-center retrospective analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28:551–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]22. Soto GJ, Frank AJ, Christiani DC, Gong MN. Body mass index and acute kidney injury in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2601–2608. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]23. Shuster A, Patlas M, Pinthus JH, Mourtzakis M. The clinical importance of visceral adiposity: a critical review of methods for visceral adipose tissue analysis. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]24. Chagnac A, Weinstein T, Korzets A, Ramadan E, Hirsch J, Gafter U. Glomerular hemodynamics in severe obesity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278:F817–F822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]25. Hutley L, Prins JB. Fat as an endocrine organ: relationship to the metabolic syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2005;330:280–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]26. Curiel-Balsera E, Munoz-Bono J, Rivera-Fernandez R, Benitez-Parejo N, et al. Consequences of obesity in outcomes after cardiac surgery. Analysis of ARIAM registry (in Spanish) Med Clin (Barc) 2013;141:100–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]27. Stamou SC, Nussbaum M, Stiegel RM, Reames MK, Skipper ER, Robicsek F, Lobdell KW. Effect of body mass index on outcomes after cardiac surgery: is there an obesity paradox? Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]28. Chao CT, Wu VC, Tsai HB, Wu CH, Lin YF, Wu KD, Ko WJ, Group N. Impact of body mass on outcomes of geriatric postoperative acute kidney injury patients. Shock. 2014;41:400–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]29. Davenport DL, Xenos ES, Hosokawa P, Radford J, Henderson WG, Endean ED. The influence of body mass index obesity status on vascular surgery 30-day morbidity and mortality. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:140–147. 147 e141; discussion 147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]30. Huang CX, Tighiouart H, Beddhu S, Cheung AK, Dwyer JT, Eknoyan G, Beck GJ, Levey AS, Sarnak MJ. Both low muscle mass and low fat are associated with higher all-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2010;77:624–629. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]31. Wong JS, Port FK, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Carroll CE, Wolfe RA, Agodoa LY, Daugirdas JT. Survival advantage in Asian American end-stage renal disease patients. Kidney Int. 1999;55:2515–2523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]32. Huang JC, Lin HY, Lim LM, Chen SC, Chang JM, Hwang SJ, Tsai JC, Hung CC, Chen HC. Body mass index, mortality, and gender difference in advanced chronic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]33. Sleeman P, Patel NN, Lin H, Walkden GJ, Ray P, Welsh GI, Satchell SC, Murphy GJ. High fat feeding promotes obesity and renal inflammation and protects against post cardiopulmonary bypass acute kidney injury in swine. Crit Care. 2013;17:R262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]34. Palomba H, de Castro I, Neto AL, Lage S, Yu L. Acute kidney injury prediction following elective cardiac surgery: AKICS Score. Kidney Int. 2007;72:624–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Cardiorenal Medicine are provided here courtesy of Karger Publishers

Author Information

aDepartment of Nephrology, Zhongshan Hospital, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai, ChinabDepartment of Cardiology Surgery, Zhongshan Hospital, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai, ChinacDepartment of Shanghai Key Laboratory of Kidney and Blood Purification, Xiamen Branch, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, ChinadDepartment of Shanghai Institute for Kidney and Dialysis, Xiamen Branch, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, ChinaeDepartment of Nephrology, Xiamen Branch, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China*Jie Teng, Department of Nephrology, Xiamen Branch, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, No. 668 Jinhu Road, Xiamen 361015 (China), E-Mail nc.hs.latipsoh-sz@eij.gnet and nc.hs.latipsoh-sz@gnaiqoaix.gnidZhouping Zou, Yamin Zhuang, and Lan Liu contributed equally to this study.

Copyright

Copyright © 2017 by S. Karger AG, Basel