Survival After a Transcranial Bihemispheric Stabbing with a Knife

Abstract

Low-velocity penetrating brain injuries (PBIs), also referred to as nonmissile brain injuries, typically result from stabbings, industrial or home accidents, or suicide attempts. A great deal of literature has focused on the injury patterns and management strategies of high-velocity PBIs. However, there are substantially fewer large, contemporary studies focused solely on low-velocity PBIs. Here, we present an interesting and uncommon case of a patient who suffered a bihemispheric stab wound involving the basal ganglia. A 22-year-old man presented to the hospital with a stab wound to the left calvarium. His initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 13, but he rapidly declined to a six and was intubated. He was emergently taken to the operating room for craniectomy, knife removal, and external ventricular drain placement. On the first postoperative day, the patient was following commands with all extremities. He was discharged to a rehabilitation facility 13 days postinjury. One year after the injury, the patient was free of major neurologic sequelae. This report illustrates a rare case of a good functional outcome after a transcranial stabbing with multiple imaging and exam findings usually associated with poor outcomes.

Keywords: penetrating brain injury, low velocity penetrating brain injury, non-missile brain injury, bihemispheric injury, transcranial stab wound

Case report

A 22 year old man was brought to a level one trauma center by emergency medical services from the scene of a stabbing. Emergency medical personnel reported the patient was found in the field with a large kitchen knife protruding from the left side of his head (Figure 1). Upon arrival, the patient was awake, alert, and moving all extremities. His initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 13. However, he subsequently became combative, declined to a GCS of six, and was intubated for airway protection.

Figure 1

The patient presented to the emergency room with a knife penetrating the calvarium in the left temporal area.(A) View of the injury from inferior to the mandible. (B) Anterior view of the injury.

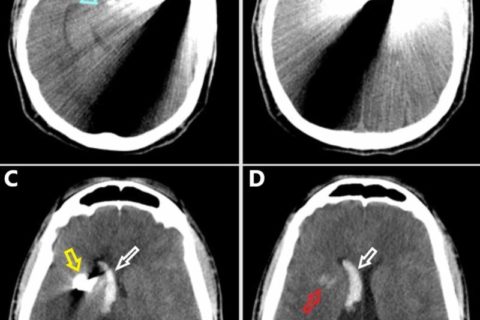

Primary and secondary surveys did not reveal additional injuries. Physical exam was significant for a large knife protruding from the left cranium approximately 10 cm. Medical history was obtained from the next of kin, which was only remarkable for illicit drug use. Laboratory investigations were remarkable for a leukocytosis of 13 K/µL and a lactate of 5.8 mmol/L. The patient was taken for noncontrasted head CT exam, which showed a moderate right lateral intraventricular hemorrhage, a small intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the right basal ganglia, a 3 mm subdural hematoma along the left cerebral convexity, and a small subarachnoid hemorrhage in the basal cisterns (Figure 2).

Noncontrasted preoperative CT scan of the head in the axial plane progressing from inferior (A) to superior (D).(A) The knife penetrates the calvarium in the left temporal region. Note the midbrain is in close proximity to the injury tract (blue arrow). (B) The knife begins to penetrate across midline. (C) The tip of the knife is evident in the right hemisphere (yellow arrow). Note the intraventricular hemorrhage in the right lateral ventricle frontal horn and body (white arrow). (D) There is a small intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the right basal ganglia (red arrow). Intraventricular hemorrhage is evident within the right lateral ventricle frontal horn and body (white arrow).

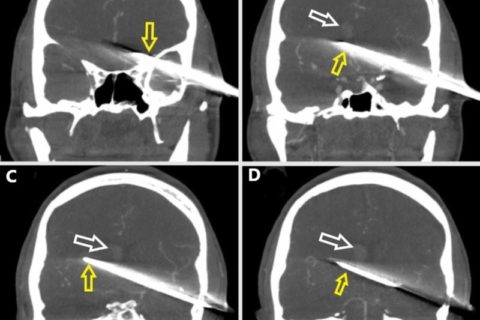

There was approximately 10 cm of intracranial penetration projecting from the left temporal bone through the left basal ganglia and ultimately terminating in the right basal ganglia. Subsequent CT angiogram of the brain did not show a definitive vascular injury, although there was significant beam artifact from the knife (Figure 3).

Coronal plane preoperative CT angiography in the vascular window setting progressing from anterior (A) to posterior (D).(A) The knife (yellow arrow) penetrates the left temporal bone. (B) The knife (yellow arrow) passes midline, and a right lateral intraventricular hemorrhage is evident (white arrow). (C) The knife is seen along the full extent of its intracranial route (yellow arrow). The right lateral intraventricular hemorrhage is evident (white arrow). (D) Posterior limit of the intracranial knife (yellow arrow). The right lateral intraventricular hemorrhage is evident (white arrow).

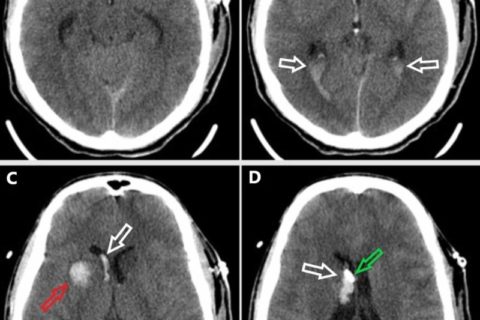

The patient was taken emergently to the operating room by the neurosurgery team. The patient received cefazolin, vancomycin, cefepime, and metronidazole prior to skin incision due to the contaminated nature of the wound. A left pterional incision was made and T’d into the knife. A left temporal craniectomy was drilled around the knife. Once the craniectomy was completed, the knife was carefully removed from the cranium. An external ventricular drain was placed after an intraoperative head CT scan showed increased hemorrhage along the injury tract. The patient’s postoperative head CT scan is shown in Figure 4.

Postoperative noncontrasted head CT scan in the axial plane progressing from inferior (A) to superior (D).(A) There is an intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the left anterior temporal lobe along the injury tract (red arrow). (B) The intraventricular blood is seen layering into the right occipital horn of the lateral ventricle and the bilateral atria (white arrows). Injury tract hemorrhage is seen in the midline (red arrow). (C) There is a tract hemorrhage within the right basal ganglia (red arrow) and intraventricular hemorrhage within the right lateral ventricle frontal horn and body (white arrow). (D) The external ventricular drain tip (green arrow) is visible adjacent to the right lateral intraventricular hemorrhage (white arrow)

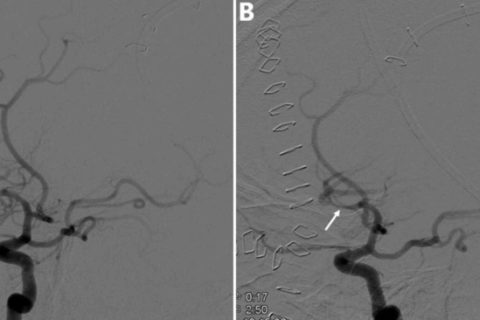

The patient was following commands with all extremities on the first postoperative day. He developed hydrocephalus requiring cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion, so the external ventricular drain was left in place for six days. A formal cerebral angiogram was done on postoperative day six showing a focal area of vasospasm of the left inferior division of the middle cerebral artery M2 segment (Figure 5). This was treated with intra-arterial verapamil with mild improvement on completion angiogram.

Digital subtraction angiography of the left internal carotid artery and its major intracranial branches six days postinjury.(A) Focal area of vasospasm in the left inferior division of the middle cerebral artery M2 segment before intra-arterial verapamil administration (white arrow). (B) Focal area of vasospasm with mild improvement in the left inferior division of the middle cerebral artery M2 segment after intra-arterial verapamil administration (white arrow).

The patient was febrile early in his postoperative course and therefore completed 12 days of broad spectrum antibiotics. Two sets of blood cultures were negative. He completed seven days of levetiracetam for early seizure prophylaxis. He was discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility 13 days postinjury. He was discharged to home from rehab on postinjury day 21. The patient has not followed up with neurosurgery since his discharge. However, he returned to the ER for suture removal almost one year after the injury and did not appear to have neurologic sequelae. Based on chart review of this visit, the patient’s Glasgow Outcome Score would be five.

Copyright © 2019, Ebeling et al.