Ulcerated Lesion of the Tongue as Manifestation of Systemic Coccidioidomycosis

1. Background

Coccidioidomycosis was first discovered in Argentina in 1892 by a medical student with the observation of several patients developing dermatologic lesions throughout the body. Works developed by clinicians and scientists at Stanford University Medical Center were the main source of knowledge of this condition. Coccidioidomycosis can be acquired by inhalation of the organism or inoculation through the skin. Different terms were used when initially described such as San Joaquin fever, Desert fever, or Valley fever, which still remain used up to now [1]. The condition is endemic in the southwest USA, northern Mexico, and parts of Central and South America [2]. Usually C. immitis grows 5–30 cm under the ground, especially around burrows of rodents and reptiles. Risk factors for acquiring this infection include activities that expose the subject to contaminated dust such as archaeologist, military personnel, construction workers, hunters, earthquakes victims, and immunocompromised patients. It is more prevalent in man than woman. Skin manifestations of coccidioidomycosis are frequent, usually as papule, nodules, and verrucous lesions that may evolve to an ulcer or abscess. The most affected areas are the nasolabial groove and sternoclavicular area [3] Coccidioidomycosis is typically a granulomatous infection involving the lungs, rarely presenting in the mouth [4].

2. Case Presentation

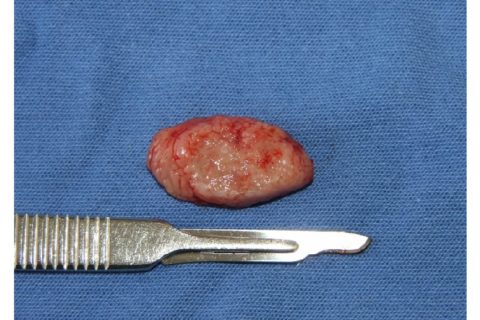

A 60-year-old man from a rural area of Saltillo, northern Mexico, came to our institution presenting an ulcerated lesion on the left lateral border of the tongue of 1.5 cm of diameter. According to the patient the lesion has been growing for the last 5 months (Figure 1). He is a nonsmoker, with no evidences of any systemic disease. Considering the clinical aspects, age of the patient, and poor oral health, epidermoid carcinoma was considered as diagnosis. After an excisional biopsy the diagnosis was of coccidioidomycosis (Figure 2).

Excisional biopsy of the lesion.

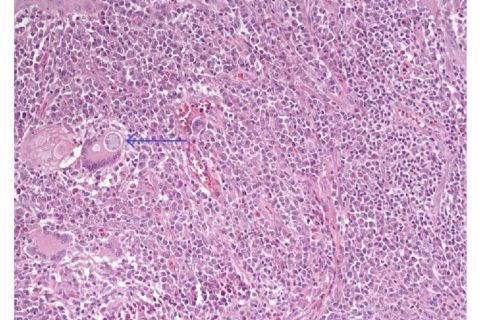

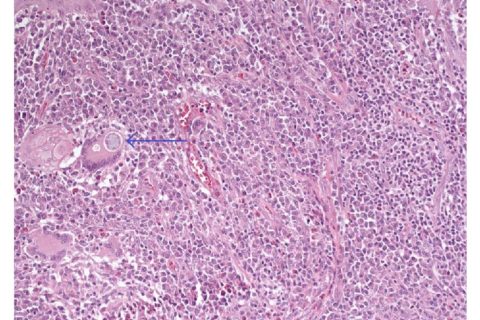

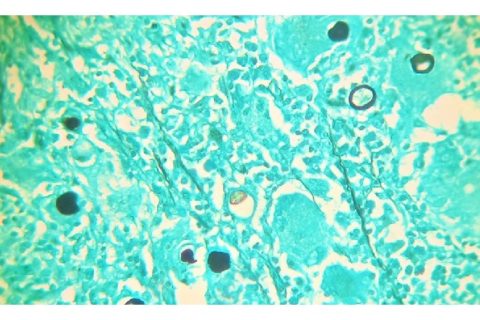

Histology demonstrated a granulomatous lesion with abundant lymphoplasmacytic chronic inflammatory infiltrate and multinucleated giant cells with spherical cytoplasmic inclusions of different size which correspond to the infectious agent C. immitis (Figures 3–6).

Chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, showing lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells containing spherical cytoplasmic inclusions corresponding to Coccidioides immitis (H&E; 200x).

C. PAS staining highlighting various bodies of C. immitis in red color (PAS).

C. Grocott staining confirming the presence of large bodies of C. immitis in black (Grocott).

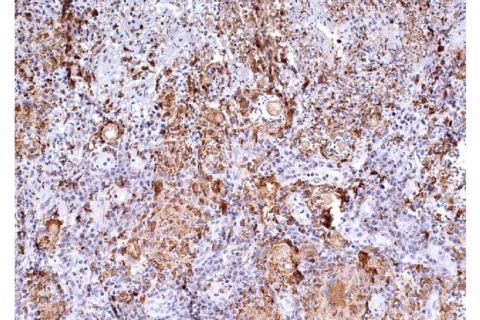

Immunohistochemistry showing granulomatous inflammation with predominance of macrophages and giant multinucleated cells positive for CD68, containing bodies of C. immitis (200x).

3. Differential Diagnosis

Ulcerated lesions of the mouth are common having variable causes; the most common are associated with trauma, infections, and epidermoid carcinoma, the latter usually presenting as a single ulcerated lesion in adults and elderly patients. Infections of the mouth causing ulcers include herpes simplex, syphilis, and depending on the immunological status of the patient and region of the world less common diseases should be considered particularly fungal infections as histoplasmosis, aspergillosis, cryptococcosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, and coccidioidomycosis. Many cases of tuberculosis have been found in the mouth and less commonly leishmaniasis and rarely hanseniasis. Early and correct diagnosis are essential for treatment and most of these diseases present systemic involvement [5, 6].

4. Treatment and Follow-Up

The patient was referred to the infectious disease department where supplementary studies were performed and systemic infection of coccidioidomycosis was confirmed and pulmonary lesions were evident on the chest X-ray. He received systemic antifungal therapy, itraconazole 200 mg tablets and 1 tablet by mouth per day during breakfast for three months, liver function tests were performed, and the results show no relevant data. Treatment was extended for another three months; we consider assessing liver function and tests were performed but this time the results were altered so it was decided to suspend the treatment for one month. Treatment was retaken for three months and by this time there was no evidence of the infection being eradicated completely; the treatment was extended for a year.

1. Hirschmann J. V. The early history of coccidioidomycosis: 1892–1945. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;44(9):1202–1207. doi: 10.1086/513202. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Ocampo-Garza J., Castrejón-Pérez A. D., Gonzalez-Saldivar G., Ocampo-Candiani J. Cutaneous coccidioidomycosis: a great mimicker. BMJ Case Reports. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-211680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Navarro L. A. M., Sauceda S. R. F. Coccidioidomicosis. Medicina Interna de Mexico. 2008;24(2):125–141. [Google Scholar]

4. Eversole L. R. Clinical Outline of Oral Pathology: Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th. Shelton, Conn, USA: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2011. [Google Scholar]

5. Burket L. W., Ship J. A., Glick M., Greenberg M. S. Burket’s Oral Medicine. 11th. Hamilton, Ont, USA: PMPH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

6. Rodriguez R. A., Konia T. Coccidioidomycosis of the tongue. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2005;129(1):e4–e6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Duggan P. T., Deegan A. P., McDonnell T. J. Case of coccidioidomycosis in Ireland. BMJ Case Reports. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-215898. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Laniado-Laborín R. Coccidioidomicosis. Más que una enfermedad regional. Revista del Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias. 2006;19(4):301–308. [Google Scholar]

9. Rosas R. C. B., Riquelme M. Epidemiología de la coccidioidomicosis en México. Revista Iberoamericana de Micología. 2007;24(2):100–105. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1406(07)70022-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Copyright © 2017 Luis A. Mendez et al.

1Basic Sciences, University of Montemorelos, School of Dentistry, Montemorelos, NL, Mexico2Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, IMSS, Saltillo, COAH, Mexico3Oral Pathology, University of Montemorelos, School of Dentistry, Montemorelos, NL, Mexico4Department of Oral Pathology, University of Campinas, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil*

Luis A. Mendez: xm.ude.mu@zednemsiulAcademic Editor: Dante Amato