Autoresuscitation: A Case and Discussion of the Lazarus Phenomenon

1. Introduction

Lazarus phenomenon or autoresuscitation (AR) is a very rare condition defined as delayed unassisted return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after cessation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) [1, 2]. After being first reported by Linko et al. in 1982 [3], it was later termed the “Lazarus phenomenon” by Bray Jr. in 1993 [4] after the biblical figure Lazarus, whom Jesus supposedly resurrected four days after his death and burial (Gospel of John Chapter 11: 1–44).

The occurrence of this phenomenon may be widely underreported as illustrated by the fact that almost 50% of French emergency physicians claim to have encountered AR in clinical practice [5] and by the statement by Dhanani et al. that more than one-third of Canadian intensivists have seen at least one case of AR [6]. The true incidence remains unknown.

2. Case Report

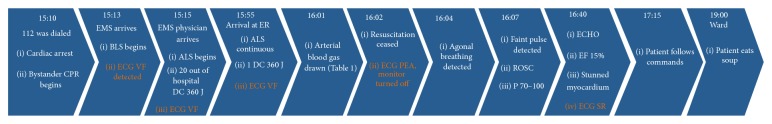

A 67-year-old Caucasian male collapsed with cardiac arrest outside his home (Figure 1). A nurse, who was caring for the patient on a daily basis, coincidently passed by and immediately initiated CPR. The emergency medical services (EMS) were called at 15:10 hours and an ambulance arrived at 15:13 and the emergency physician at 15:15. On arrival, the initial rhythm was ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation was performed according to the advanced life support (ALS) algorithm [7] including chest compression, ventilation, intubation in the field, a total of 20 defibrillations, and standard drug administration, including epinephrine and amiodarone.

A 67-year-old Caucasian male collapsed with cardiac arrest outside his home (Figure 1). A nurse, who was caring for the patient on a daily basis, coincidently passed by and immediately initiated CPR. The emergency medical services (EMS) were called at 15:10 hours and an ambulance arrived at 15:13 and the emergency physician at 15:15. On arrival, the initial rhythm was ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation was performed according to the advanced life support (ALS) algorithm [7] including chest compression, ventilation, intubation in the field, a total of 20 defibrillations, and standard drug administration, including epinephrine and amiodarone.

The patient had massive comorbidity on the basis of universal atherosclerosis due to 31 pack years of smoking, severe hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and heredity. In 2004, bilateral in situ bypass surgery optimised blood flow to his lower extremities. He was also diagnosed with left ventricular hypertrophy and systolic and diastolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction (EF) of 40%. In 2006, the patient underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery, complicated by postoperative ventilator therapy for one month, middle cerebral artery infarction, sternal infection, and organic delirium, which elapsed into a psychotic episode and severe depression. In the last three years, the patient had been depending on haemodialysis three times a week. Furthermore, the medical history included severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a forced expiratory vital capacity of 45%, abdominal aortic aneurism of 5.1 cm, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, and chronic musculoskeletal pain due to cervical and lumbal spinal stenosis. His medication comprised carvedilol, ramipril, simvastatin, warfarin, inhaled salmeterol/fluticasonpropionat, inhaled tiotropium, pantoprazole, paracetamol, vitamins and, related to his hemodialysis, alfacalcidol, erythropoietin, phosphate-binding drug, and furosemide.

Nearly an hour after the cardiac arrest at 15:55 the patient arrived at the emergency department still in ventricular fibrillation. Upon arrival, he was defibrillated again. At the next rhythm check, the ECG monitor showed pulseless electrical activity (PEA) with very slow bizarre looking complexes. The decision to stop resuscitation efforts was taken at 16.02, and the monitors were turned off. This was also based on appearing information from the patient’s medical files that within the previous three years he had repeatedly rejected resuscitation attempts in the case of respiratory or circulatory arrest. Two minutes later, slow agonal (gasping) breathing was seen, and five minutes later a very faint central pulse was detected. Arterial blood gas (ABG) taken in the last minute of resuscitation had now been analyzed and implied severe metabolic acidosis and hypokalemia (Table 1). An echocardiography (ECHO) showed general hypokinesia with an EF of 15% (see Videos 1 and 2 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/724174). The decision not to resume treatment was upheld, whereas palliative care was continued also on suspicion of hypoxic brain damage. Surprisingly, the patient regained consciousness. One hour later, he blinked and squeezed hands on command. Three hours later he sat up in his bed and had some soup (Figure 1).

The patient was considerably unfound with being resuscitated and refused any further treatment. He was not psychotic and had the capability of making his own decisions. Twenty-two hours after the initial cardiac arrest, he died.