Motor vehicle accident

Author information

1Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

2Department of Neurosurgery, Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

3Department of Surgery, Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

Correspondence to Dr Faiz U Ahmad, ude.yrome@damha.ziaf

Case presentation

A 29-year-old man was brought to our level one trauma hospital after a motor vehicle accident, during which he was ejected from the vehicle during the crash. He lost consciousness on impact but was alert and oriented on arrival at the hospital, and was able to move all four extremities during the initial trauma assessment.

Multiple injuries were noted on presentation, including an extensive degloving injury with anorectal dissociation. The patient was taken for an emergent exploratory laparotomy shortly after admission and his abdomen was left open with a temporary covering for 2 days due to abdominal compartment syndrome. Subsequent surgeries included bilateral chest-tube placement, end-sigmoid colostomy, anorectal reconstruction, closed reduction of a tibial fracture and tracheostomy.

On hospital day 3, the patient’s neurological status deteriorated to a Glasgow Coma Scale of 3 T, with reactive pupils but no cough or gag reflex on examination. A head CT showed diffuse cerebral oedema due to a traumatic brain injury. On hospital day 7, he developed sepsis with renal failure and increased need for respiratory and blood pressure support. At that time, he was found to have necrotising fasciitis, and required multiple operative debridements of the devitalised skin and soft tissue.

Investigations

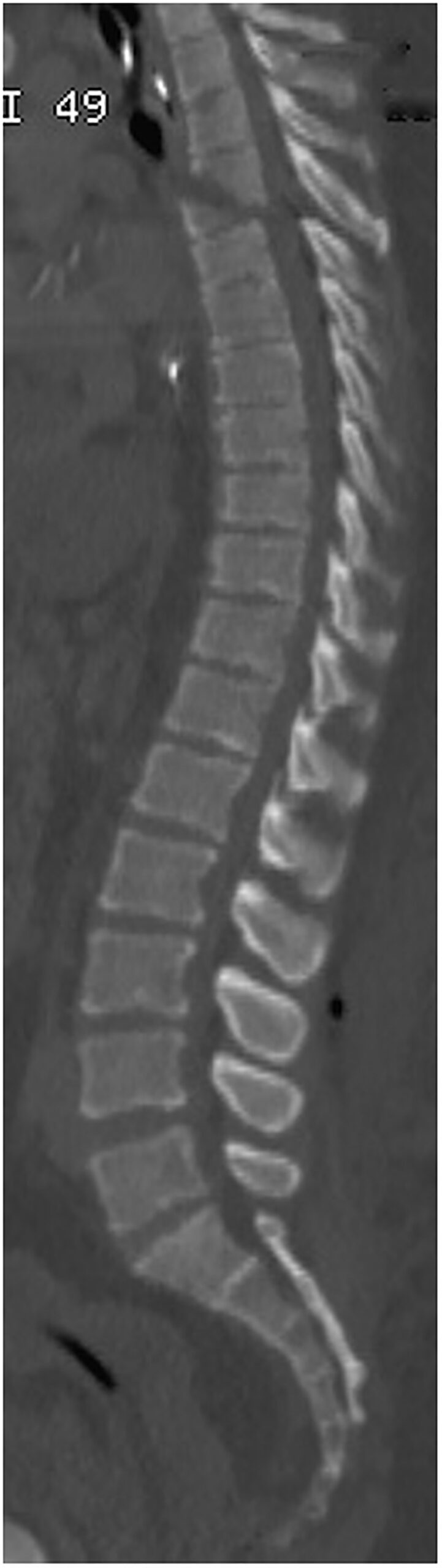

At the time of admission, CT imaging of the spine demonstrated an acute, oblique fracture through the body of the T4 and bilateral widening of the facet joints at T4/5, with posterior displacement of the fracture causing spinal cord compression (figure 1), consistent with an AO/Magerl Type B2.2.2 injury. Owing to the patient’s other injuries and haemodynamic instability, no further imaging could be obtained to assess injury to the spinal cord and ligamentous structures.

Sagittal CT scan demonstrating thoracic chance fracture after motor vehicle accident.

On admission, sensation and motor function were intact in all four extremities, but after the patient’s mental status declined secondary to traumatic brain injury, spinal cord function was difficult to monitor. When his condition improved, he had full strength in his upper extremities and was able to follow commands in his lower extremities. There was no loss of sensation detectable on examination. Spinal cord function appeared to be preserved although this was difficult to assess due to his other injuries.

Treatment

On hospital day 9, the patient’s neurological status began to improve and he no longer required pressors for haemodynamic stability. Over the next 3 weeks, he was frequently brought to the operating room for wound irrigation and debridements with revisions of his abdominal closure. During that time, his vital signs and renal function slowly improved and he was extubated on hospital day 25.

Owing to the patient’s numerous injuries and haemodynamic instability, immediate management of the thoracic spine fracture consisted of a thoraco-lumbar-sacral orthosis (TLSO) brace, though the brace had to be frequently removed for wound care. One month into the hospitalisation, with his condition better stabilised, attention returned to the vertebral fracture and options for management. The constellation of features found on CT was consistent with an unstable chance fracture, which required surgical stabilisation.

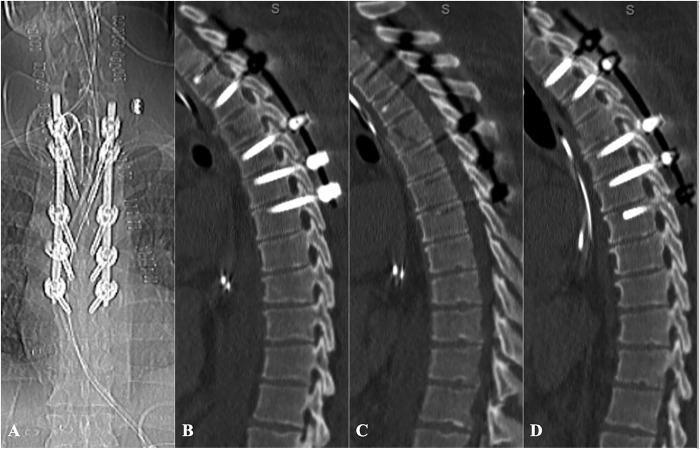

Though the patient’s condition was improving, he was not a good candidate for open surgery due to necrotising fasciitis, and extensive loss of skin and subcutaneous tissue. This resulted in a large area of exposed muscle over the lower thoracolumbar spine (figure 2). In light of this, surgical stabilisation was achieved using a minimally invasive approach, with percutaneous placement of pedicle screws from T2–T7 with bilateral titanium rods (figure 3). The pedicle screws were 5 mm by 40 mm in size and were made by DePuy-Synthes (Raynam, Massachusetts, USA).

The decision to instrument down to the T7 level was due to difficulty in distinguishing the T4-6 levels on fluoroscopy after the T4 fracture was reduced, and the inability to cannulate and instrument the T4 pedicles. Therefore, we erred on the side of caution to provide an extra level of instrumentation and support. The patient tolerated the procedure well and postoperative imaging demonstrated accurate placement of hardware and effective reduction and fixation of the chance fracture (figure 4).

Postoperative anteroposterior radiograph (A), sagittal CT through the left pedicles (B), mid-sagittal CT (C), and sagittal CT through the right pedicles (D) demonstrating fracture reduction and successful placement of pedicle screw fixation for thoracic AO/Magerl Type B2.2.2 fracture.

Outcome and follow-up

In the weeks following surgery, the patient continued to improve and received several skin grafts to the areas of exposed subcutaneous tissue. He was transferred from the intensive care unit to a regular floor, and was subsequently discharged to an acute rehabilitation facility. His total length of hospital stay was 12 weeks.

His motor strength and lower extremity function improved tremendously with extensive physical therapy, and at his most recent follow-up appointment (14 months) he was able to walk independently and perform all basic activities of daily life. Radiographs taken after surgery demonstrated accurate hardware placement and normal alignment of the thoracic spine (figure 4). Follow-up photographs (figure 5) demonstrated well-healed surgical incisions and well-incorporated skin grafts covering the previously exposed soft tissue over the thorax and gluteus.

Figure 5

Photograph demonstrating healed surgical incisions and incorporated skin grafts after extensive degloving injury from motor vehicle accident, taken 14 months after the initial injury.

References

1. Marchan EM, Ghobrial GM, Harrop JS. Thoracolumbar spine fractures. In: Benzel E, ed. Spine. 1. 3rd edn Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2012:413–19. [Google Scholar]

2. Saboe LA, Reid DC, Davis LA et al. . Spine trauma and associated injuries. J Trauma 1991;31:43–8. 10.1097/00005373-199101000-00010 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. van Beek EJ, Been HD, Ponsen KK et al. . Upper thoracic spinal fractures in trauma patients—a diagnostic pitfall. Injury 2000;31:219–23. 10.1016/S0020-1383(99)00235-1 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Joaquim A, Patel A. Thoracolumbar fractures. In: Browner L, Jupiter JB, Krettek C, et al., eds, editors. Skeletal Trauma: Basic Science, Management, and Reconstruction. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2009:911–79. [Google Scholar]

5. Petitjean ME, Mousselard H, Pointillart V et al. . Thoracic spinal trauma and associated injuries: should early spinal decompression be considered? J Trauma 1995;39:368–72. 10.1097/00005373-199508000-00030 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Dalbayrak S, Yaman O, Yilmaz T. Current and future surgery strategies for spinal cord injuries. World J Orthop 2015;6:34–41. 10.5312/wjo.v6.i1.34 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Aebi M. Classification of thoracolumbar fractures and dislocations. Eur Spine J 2010;19(Suppl 1):S2–7. 10.1007/s00586-009-1114-6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]8. Herkowitz HN, Garfin SR. Rothman-Simeone The Spine. 6th edn Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2011. [Google Scholar]

9. Grossbach AJ, Dahdaleh NS, Abel TJ et al. . Flexion-distraction injuries of the thoracolumbar spine: open fusion versus percutaneous pedicle screw fixation. Neurosurg Focus 2013;35:E2 10.3171/2013.6.FOCUS13176 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Liu Y-J, Chang M-C, Wang S-T et al. . Flexion-distraction injury of the thoracolumbar spine. Injury 2003;34:920–3. 10.1016/S0020-1383(02)00396-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Bliemel C, Lefering R, Buecking B et al. . Early or delayed stabilization in severely injured patients with spinal fractures? Current surgical objectivity according to the Trauma Registry of DGU: treatment of spine injuries in polytrauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;76:366–73. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182aafd7a [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. McAnany S, Overley S, Kim J et al. . A Meta-analysis On The Treatment Of Thoracolumbar Fractures: Open Versus Percutaneous Fixation. Poster. Chicago, IL, 9–10 April 2015. Report No: 1092-0684 Contract No. 4. [Google Scholar]

13. Spitz SM, Sandhu FA, Voyadzis JM. Percutaneous “K-wireless” pedicle screw fixation technique: an evaluation of the initial experience of 100 screws with assessment of accuracy, radiation exposure, and procedure time. J Neurosurg Spine 2015;22:422–31. 10.3171/2014.11.SPINE14181 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]14. Scaramuzzo L, Tamburrelli FC, Piervincenzi E et al. . Percutaneous pedicle screw fixation in polytrauma patients. Eur Spine J 2013;22(Suppl 6):S933–8. 10.1007/s00586-013-3011-2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Lee J-K, Jang J-W, Kim T-W et al. . Percutaneous short-segment pedicle screw placement without fusion in the treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures: is it effective?: comparative study with open short-segment pedicle screw fixation with posterolateral fusion. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013;155:2305–12; discussion 12 10.1007/s00701-013-1859-x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Schizas C, Kosmopoulos V. Percutaneous surgical treatment of chance fractures using cannulated pedicle screws. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg Spine 2007;7:71–4. 10.3171/SPI-07/07/071 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]