Orbital myiasis

Yan-Ling Huang, MD,a Lu Liu, MD,c Hao Liang, MD,a Jian He, MD,a Jun Chen, MD,a Qiao-Wen Liang, MD,a Zhi-Yuan Jiang, MD,b Jian-Feng He, MD,a,∗ Min-Li Huang, MD,a,∗ and Yi Du, MDa,∗

Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

1. Introduction

Maggots are larvae of Diptera flies, most of which are mainly found in human and animal feces, garbage, decaying plants and animal carcasses and feed on feces and decaying organic matter. In cases of accidents or in certain specific species, they can infest vertebrate animals, including humans, and feed on living or dead tissue, as well as on body fluids,[1] leading to myiasis. Myiasis mainly occurs in animals such as cattle, goats and pigs but occasionally occurs in humans.[2] Advanced age, disease-ridden status, poor self-care, poor hygiene, and rural background are reported risk factors for human myiasis. A pastoral or rural background provides the conditions for the prevalence of myiasis because it is a zoonotic disease. Myiasis is mainly prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions, where a warm and humid climate prevails almost throughout the year,[1] or in developing countries with a large population density and poor sanitation.

Ophthalmomyiasis can involve the eye, orbit, and periorbital tissues. It is classified as external, internal or orbital in accordance with the site of the larvae infestation.[3] Limited superficial infestation of external ocular tissues such as the palpebra and conjunctiva is called external ophthalmomyiasis. When the larvae invade deeply and migrate into the subretinal space, internal ophthalmomyiasis occurs. Orbital myiasis is a more extensive infestation involving orbital tissue and is the most serious form. Once established, orbital myiasis progresses rapidly and can completely destroy the orbital tissues within days.[4] Fortunately, it is the least common form,[5] with only a few cases reported. Management of orbital myiasis ranges from simple manual removal of the maggots to destructive surgeries of the globe and orbit.[6]

Medical professionals are unfamiliar with orbital myiasis because it is such a rare disease, which may increase the difficulty of recognition and treatment. Here, we report a case of orbital myiasis and conduct a systematic literature review of cases previously reported in the literature, aiming to better outline the clinical features and therapeutic management of orbital myiasis. The patient himself consented to the publication of the study. This case report was approved by the ethics review committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, (2019-KY-E-036), Nanning, China, and an informed consent form was signed by the patient himself.

2. Case report

A 72-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department on October 31, 2015, with a complaint of repeated pain for two years after trauma to his right eyelid and a 2-day history of symptoms aggravated by the wriggling out of larvae. The patient reported that his right upper lid had been injured by cane leaves 2 years prior, but no treatment was received. Then, he experienced repeated pain in his right eye, accompanied by gradually decreased vision until it was completely lost 1 year previously. His painful symptoms worsened 2 days before presentation, with bleeding, a crawling sensation and larvae wriggling out (Fig. (Fig.1).1). He denied a history of alcoholism, previous ocular surgery, or prolonged use of medications.

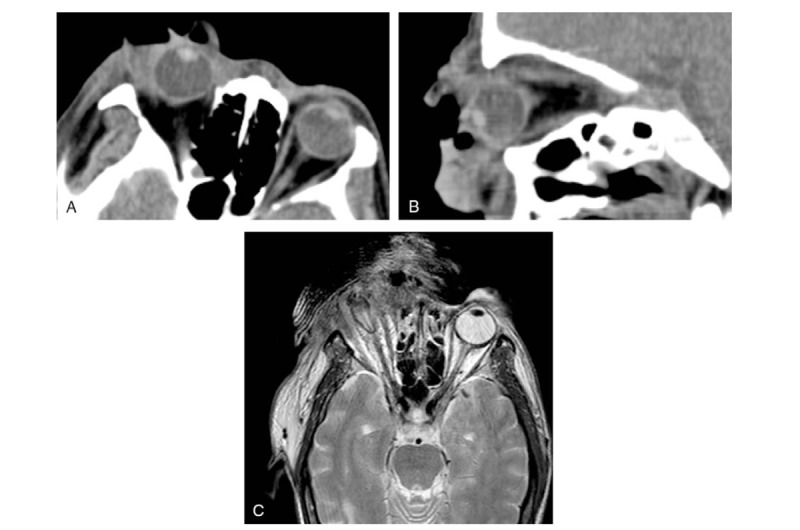

On ophthalmic examination, the visual acuity test revealed no light perception in his right eye. His right periorbital skin was red and edematous, and the eyelid was thickened. There was a large eyelid wound of approximately 4 cm ∗ 1 cm filled with numerous white larvae, some of which were crawling out. No abnormalities were found in the left eye or upon systemic examination. A computed tomography scan revealed that the right eyeball protruded and that the soft tissues around it were swollen (Fig. (Fig 2). Two days later, magnetic resonance imaging showed that the shape of the right eyeball was changed and that the normal structure of the eyeball could not be identified (Fig. 2). A diagnosis of orbital myiasis was made.

(A and B) An orbital computed tomography scan showed that right eyeball protrusion and periocular soft tissue edema. Two days later, (C) magnetic resonance imaging showed that the shape of the right eyeball was changed and the normal structure of the eyeball could not be identified.

Considering potential infections, the patient received topical levofloxacin eye drops, intravenous ceftazidime and levofloxacin, and a tetanus antitoxin injection. In view of imaging evidence of total destruction of the globe caused by infiltration of the larvae, exenteration of the right orbit was performed in the patient. All necrotic tissues and nearly 100 larvae were removed. Then, the wound was closely observed for infections and possibly missed larvae. Within three days after surgery, there were still 3 larvae crawling out of the orbit. On the ninth postoperative day, the defect was repaired via reconstruction with a pedicled musculocutaneous flap from the forehead region (Fig. (Fig.3).3). The patient recovered well postoperatively and was discharged uneventfully. During the 6-month follow-up period, the wound healed well, and the patient had no further complaints. Subsequently, he was lost to follow-up.

The second week after orbit exenteration and frontal flap reconstruction.

The histopathological examination of the orbital contents revealed hyperplastic inflammatory granulation tissue, large areas of necrotic tissue and acute inflammatory exudates. The larvae were identified as the larvae of Lucilia sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae) (Fig. (Fig.4A and B).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Lu Liu, Hao Liang, Jian He, Jun Chen, Qiao-Wen Liang, Zhi-Yuan Jiang, Yi Du.

Data curation: Yan-Ling Huang, Lu Liu, Hao Liang.

Formal analysis: Yan-Ling Huang.

Funding acquisition: Yi Du.

Methodology: Jian He, Jun Chen, Qiao-Wen Liang, Zhi-Yuan Jiang, Yi Du.

Project administration: Yi Du.

Resources: Lu Liu, Hao Liang.

Supervision: Hao Liang, Jian-Feng He, Min-Li Huang, Yi Du.

Writing – original draft: Yan-Ling Huang, Lu Liu, Jian He, Jun Chen, Qiao-Wen Liang, Yi Du.

Writing – review & editing: Zhi-Yuan Jiang, Jian-Feng He, Min-Li Huang, Yi Du.

Yi Du orcid: 0000-0003-4879-5159.

References

[1] Bhola N, Jadhav A, Borle R, et al. Primary oral myiasis: a case report. Case Rep Dent 2012;2012:734234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][2] Carvalho RW, Santos TS, Antunes AA, et al. Oral and maxillofacial myiasis associated with epidermoid carcinoma: a case report. J Oral Sci 2008;50:103–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][3] Ozyol P, Ozyol E, Sankur F. External ophthalmomyiasis: a case series and review of ophthalmomyiasis in Turkey. Int Ophthalmol 2016;36:887–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][4] Khataminia G, Aghajanzadeh R, Vazirianzadeh B, et al. Orbital myiasis. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2011;6:199–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][5] Padhi TR, Das S, Sharma S, et al. Ocular parasitoses: a comprehensive review. Surv Ophthalmol 2017;62:161–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][6] Kaeley N, Kaushik RM, Rajput R, et al. Orbital myiasis with scalp pediculosis and buccal abscess-an uncommon presentation. J Clin Diagn Res 2017;11:OD01–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][7] Francesconi F, Lupi O. Myiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012;25:79–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][8] Agarwal DC, Singh B. Orbital myiasis–a case report. Indian J Ophthalmol 1990;38:187–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][9] Rocha EM, Yvanoff JL, Silva LM, et al. Massive orbital myiasis infestation. Arch Ophthalmol 1999;117:1436–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][10] Baliga MJ, Davis P, Rai P, et al. Orbital myiasis: a case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001;30:83–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][11] Caca I, Unlu K, Cakmak SS, et al. Orbital myiasis: case report. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2003;47:412–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][12] Osorio J, Moncada L, Molano A, et al. Role of ivermectin in the treatment of severe orbital myiasis due to Cochliomyia hominivorax. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:e57–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][13] Jain A, Desai RU, Ehrlich J. Fulminant orbital myiasis in the developed world. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91:1565–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][14] Raina UK, Gupta M, Kumar V, et al. Orbital myiasis in a case of invasive basal cell carcinoma. Oman J Ophthalmol 2009;2:41–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][15] Abalo-Lojo JM, Lopez-Valladares MJ, Llovo J, et al. Palpebro-orbital myiasis in a patient with basal cell carcinoma. Eur J Ophthalmol 2009;19:683–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][16] Yeung JC, Chung CF, Lai JS. Orbital myiasis complicating squamous cell carcinoma of eyelid. Hong Kong Med J 2010;16:63–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][17] Kamal S, Bodh SA, Kumar S, et al. Orbital myiasis complicating squamous cell carcinoma in xeroderma pigmentosum. Orbit 2012;31:137–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][18] Pandey TR, Shrestha GB, Sitaula RK, et al. A Case of orbital myiasis in recurrent eyelid basal cell carcinoma invasive into the orbit. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med 2016;2016:2904346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][19] Kersten RC, Shoukrey NM, Tabbara KF. Orbital myiasis. Ophthalmology 1986;93:1228–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][20] Maurya RP, Mishra D, Bhushan P, et al. Orbital myiasis: due to invasion of larvae of flesh fly (Wohlfahrtia magnifica) in a child; rare presentation. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med 2012;2012:371498. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][21] Puthran N, Hegde V, Anupama B, et al. Ivermectin treatment for massive orbital myiasis in an empty socket with concomitant scalp pediculosis. Indian J Ophthalmol 2012;60:225–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][22] Misra N, Gogri P, Misra S, et al. Orbital myiasis caused by green bottle fly. Australas Med J 2013;6:504–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][23] Kalamkar C, Radke N, Mukherjee A. Orbital myiasis in eviscerated socket and review of literature. BMJ Case Rep 2016;2016:bcr2016215361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][24] Hall MJ, Wall RL, Stevens JR. Traumatic myiasis: a neglected disease in a changing world. Ann Rev Entomol 2016;61:159–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][25] Wood TR, Slight JR. Bilateral orbital myiasis. Report of a case. Arch Ophthalmol 1970;84:692–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][26] Balasubramanya R, Pushker N, Bajaj MS, et al. Massive orbital and ocular invasion in ophthalmomyiasis. Can J Ophthalmol 2003;38:297–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][27] De Tarso P, Pierre-Filho P, Minguini N, et al. Use of ivermectin in the treatment of orbital myiasis caused by Cochliomyia hominivorax. Scand J Infect Dis 2004;36:503–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][28] Hira PR, Assad RM, Okasha G, et al. Myiasis in Kuwait: nosocomial infections caused by lucilia sericata and Megaselia scalaris. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004;70:386–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][29] Jang M, Ryu SM, Kwon SC, et al. A case of oral myiasis caused by Lucilia sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 2013;51:119–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][30] Mircheraghi SF, Mircheraghi SF, Ramezani Awal Riabi H, et al. Nasal nosocomial myiasis infection caused by Chrysomya bezziana (Diptera: Calliphoridae) following the septicemia: a case report. Iran J Parasitol 2016;11:284–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][31] Gupta SK, Nema HV. Rhino-orbital-myiasis. J Laryngol Otol 1970;84:453–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][32] Mathur SP, Makhija JM. Invasion of the orbit by maggots. Br J Ophthalmol 1967;51:406–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][33] Sachdev MS, Kumar H, Roop, et al. Destructive ocular myiasis in a noncompromised host. Indian J Ophthalmol 1990;38:184–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][34] Teh CH, Nazni WA, Lee HL, et al. In vitro antibacterial activity and physicochemical properties of a crude methanol extract of the larvae of the blow fly Lucilia cuprina. Med Vet Entomol 2013;27:414–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][35] Teh CH, Nazni WA, Nurulhusna AH, et al. Determination of antibacterial activity and minimum inhibitory concentration of larval extract of fly via resazurin-based turbidometric assay. BMC Microbiol 2017;17:36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar][36] Valachova I, Takac P, Majtan J. Midgut lysozymes of Lucilia sericata – new antimicrobials involved in maggot debridement therapy. Insect Mol Biol 2014;23:779–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][37] Devoto MH, Zaffaroni MC. Orbital myiasis in a patient with a chronically exposed hydroxyapatite implant. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;20:395–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][38] Costa DC, Pierre-Filho Pde T, Medina FM, et al. Use of oral ivermectin in a patient with destructive rhino-orbital myiasis. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:1018–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar][39] Tomy RM, Prabhu PB. Ophthalmomyiasis externa by Musca domestica in a case of orbital metastasis. Indian J Ophthalmol 2013;61:671–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Medicine are provided here courtesy of Wolters Kluwer Health