Recurrent Vitreomacular Traction in a Patient Treated with Ocriplasmin: A Case Report

Abstract

Introduction

To describe a case of recurrent vitreomacular traction and macular edema that appeared both before and after the intravitreal injection of ocriplasmin.

Case Report

An 82-year-old monocular man presented with metamorphopsia and reduced vision of 1-week duration. The patient’s general medical history was unremarkable. His ophthalmic history was significant for severe ocular trauma in the right eye in childhood that caused phthisis. The left eye had undergone uncomplicated phacoemulsification 3 months earlier and the 1-month postoperative best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was logarithmic mean angle of resolution (logMAR) 0.0. There was no history of other ocular conditions. At presentation, BCVA was logMAR 0.2 and optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed the presence of cystoid macular edema caused by vitreomacular traction (VMT). The patient was scheduled for intravitreal ocriplasmin injection. Prior to treatment, the vision improved spontaneously to logMAR 0.1, and no VMT could be detected with spectral domain (SD)-OCT. The ocriplasmin injection was deferred but 3 weeks later the patient presented again with metamorphopsia, while VMT was again evident on SD-OCT. Ocriplasmin was injected and 1 month later the BCVA reached logMAR 0.1 without VMT. However, at 2 months post injection the VMT reappeared and a conservative approach with observation and topical nepafenac administration was decided. At the 3-month post-injection visit there was no VMT. More than 3 years after the ocriplasmin injection there is still no evidence of VMT, the patient is free of metamorphopsia, and his BCVA is logMAR 0.0.

Conclusion

Separation of consecutive layers of the vitreous cortex (vitreoschisis) may account for recurrent VMT.

Key Summary Points

| As the optimal treatment strategy for symptomatic vitreomacular traction (VMT) remains unclear, individualizing the therapeutic course of action for each patient is necessary. |

| In recent years, ocriplasmin administered intravitreally has been available for the treatment of VMTs that conform to certain morphological features. |

| As highlighted by the current case, vitreoschisis might affect the natural history of VMT, and potentially influence the response to ocriplasmin. |

Introduction

In the last several years it has become increasingly recognized that the structure and dynamic changes of the vitreous are significantly more complex than previously assumed [1–7]. Age-related changes in the structure of the vitreous may lead to the formation of vitreomacular traction (VMT) [5, 6, 8, 9], a potentially sight-threatening condition that often calls for surgical intervention [10]. The introduction of ocriplasmin (Jetrea; ThromboGenics NV, Leuven, Belgium), a recombinant protein of the protease plasmin that severs VMTs by acting on connective tissue elements of the vitreoretinal interface such as fibronectin and laminin [11], has offered a minimally invasive treatment option [10, 12].

The aim of this article is to present a case with unusual response to the intravitreal administration of ocriplasmin for the treatment of VMT.

Case Report

An 82-year-old monocular man attended the outpatient unit with complains of metamorphopsia and reduced vision of 1-week duration in his only eye. The patient’s general medical history was significant for arterial hypertension treated with metoprolol, balloon angioplasty, and cardiac pacemaker insertion several years previously. His ophthalmic history was significant for severe ocular trauma in the right eye in childhood, which eventually caused phthisis. His left eye had undergone uncomplicated phacoemulsification 3 months previously in our center and according to the patient’s charts the 1-month postoperative best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was logarithmic mean angle of resolution (logMAR) 0.0. There was no history of other ocular conditions. Written informed consent for the publication of this report was obtained from the patient.

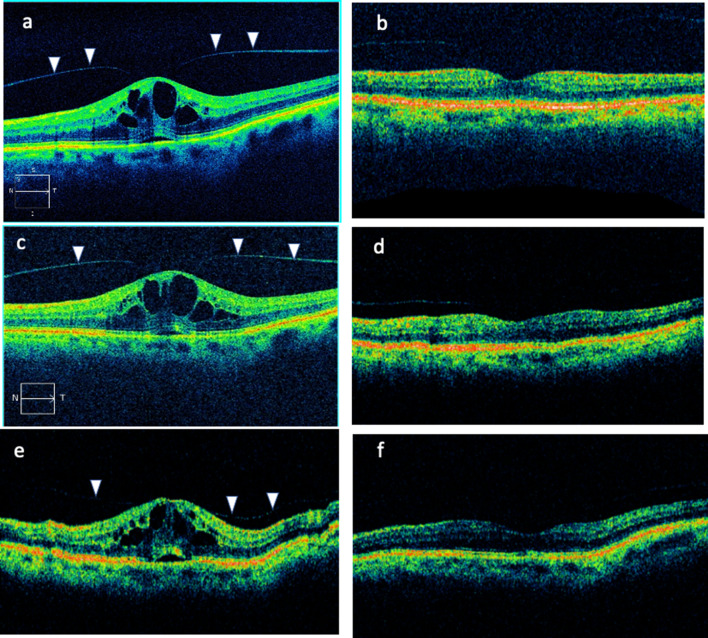

At presentation, the patient’s BCVA was logMAR 0.2, the Amsler test was positive, and cystoid macular edema was evident. The rest of the ophthalmic examination was unremarkable. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed the presence of cystoid macular edema due to VMT (Fig. 1a). No breaks were found at the peripheral retina. On the basis of these findings, the patient was scheduled for ocriplasmin injection. On the day the ocriplasmin injection was scheduled, the patient reported that his vision had spontaneously improved. Indeed, BCVA was logMAR 0.1 and no VMT could be detected (Fig. 1b). Consequently, the ocriplasmin injection was not administered.

a–f Optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging for the reported case. Figures a and c were acquired using a Zeiss spectral domain OCT, whereas all other figures were acquired using a Status OCT device. Vitreomacular traction is indicated with arrowheads

Three weeks later the patient presented with complains of metamorphopsia, while VMT was evident on OCT (Fig. 1c). Ocriplasmin was injected, and at the 1-month post-injection visit the patient’s BCVA was logMAR 0.1 without evidence of VMT (Fig. 1d). However, at the 2-month post-injection visit, VMT reappeared (Fig. 1e). After counseling with the patient, conservative management with observation and topical administration of nepafenac three times daily was advocated.

At the 3-month post-injection visit there was no VMT, while BCVA was logMAR 0.0 (Fig. 1f). More than 3 years after the ocriplasmin injection the patient is free of metamorphopsia and VMT, while BCVA remains logMAR 0.0.

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/